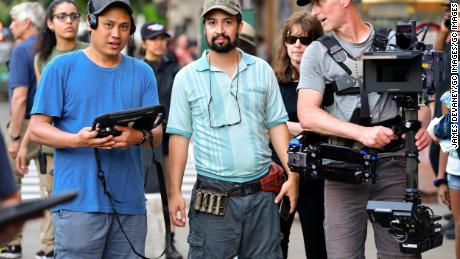

'In The Heights' musical hits the big screen

Ed Morales (@SpanglishKid) is a journalist and lecturer at Columbia University’s Center for the Study of Ethnicity and Race and the Craig Newmark Graduate School of Journalism at CUNY. He’s the author of the book “Latinx: The New Force in American Politics and Culture.” The views expressed are his own. View more opinion articles on CNN.

(CNN)From its opening sequence, Lin Manuel Miranda’s new film “In the Heights” (adapted from the stage musical of the same name) spells out its Disney-ish conceit for the audience. “Once upon a time in a far-away land called Nueva York,” his lead character Usnavi, played by Anthony Ramos, assures a group of small children seated around him at a mythical Caribbean beach. “The streets were made of music.”

From there, the audience is constantly reminded that those streets were also made of light-and-sweet coffee from uptown bodegas, a smorgasbord of Caribbean cuisine, sex-positive beauty salon gossip, and of course, hot salsa and merengue dancing. But as this extended piece of eye and ear candy unfolds, one has to wonder, haven’t we seen this before? Does representation of Latinos in the US always come down to these what might be called positive stereotypes, a kind of endless Busby Berkeley routine previously tropicalized in works like “West Side Story,” “The Mambo Kings” and “La Bamba?”

Ultimately, “In the Heights,” for all its wholesome escapism, also reveals the limits of Hollywood’s idea of representation.

With its $55 million budget, this nearly two and a half hour extravaganza has been positioned to take a lead role in American film-goers’ return to the theaters this summer. Delayed by a year because of the pandemic, and even longer than that because studios wanted big-name casting, “In the Heights” wants to shake you out of your Netflix slumber with a form of feel-good musical magic that some think is rapidly becoming obsolete.

JUST WATCHED

‘Crazy Rich Asians’ director on diversity in Hollywood and new movie ‘In the Heights’

MUST WATCH

The formula is well-executed: take one part lyricist/rapper Miranda, a helping of “Crazy Rich Asians” director Jon M. Chu, and a dash of choreographer Christopher Scott, who worked on one of the “Step Up” dance films with Chu, and you should have a massive success. This is borne out on many levels: Star turns by Anthony Ramos, Melissa Barrera (Vanessa), Leslie Grace (Nina) and Corey Hawkins (Benny) can make them more viable as bankable performers, and much of the Latino cast stands out in a moment when overall in Hollywood, actors of their background have very little visibility.

Many of the themes of Latino life in the US, such as struggles with debt, racial and ethnic discrimination and the difficulty of acculturating are put on display with competence and precision in this film. The characters’ rhyme-spitting in English, Spanish and Spanglish, a central part of the tricky task of portraying its fusion of African- and Anglo-American culture and language with home country tradition, is spot on for the most part.

JUST WATCHED

Lin-Manuel Miranda sings for separated families

MUST WATCH

The political urgency of the original Broadway production seems to have been toned down a bit, however — particularly when it comes to the gentrification that menaces urban barrios like Washington Heights. The opening sequence of the film promises a meditation on “a block that was disappearing,” and there are some allusions to demographic change in which wealthier renters, homeowners and shopkeepers push up rent prices to threaten affordability of the residents. A new dry cleaner wants to charge inflated prices, sending shock waves to eye-rolling residents, a beauty salon business is being forced to move out; an entire way of life for a long-time Latino barrio is on shaky ground.

But overall, the film focuses more on the love stories between the lead character, reluctant bodega owner Usnavi and aspiring graphic artist Vanessa, as well as the romance between Stanford undergraduate Nina, who is Puerto Rican, and taxi dispatcher Benny, who is African-American. To its credit, “In the Heights” does address some real-world social issues relevant to Washington Heights, such as the difficulty faced by urban Latinos who decide to attend elite universities. Nina expresses strong reluctance to return to Stanford in part because of micro-aggressions she receives from fellow students — on one occasion, her White roommate accuses her of stealing jewelry from her. But despite the many Dominican characters there’s little focus in the film on the Afro-Dominican world of the real Washington Heights.

JUST WATCHED

Goya CEO under fire for false Trump election claims

MUST WATCH

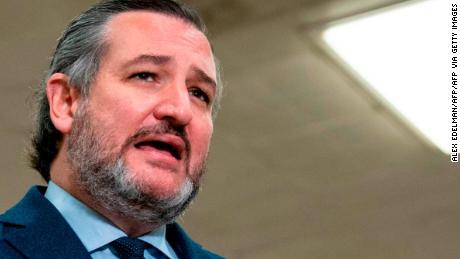

Much of the action also centers around Usnavi’s bodega, the small convenience store that has become the ultimate signifier of urban authenticity — so much so that New York City Mayoral Candidate Andrew Yang posted a video professing his love for them. Its cramped spaces are the site of intimate conversations about life and awkward flirtation. Even as Usnavi approaches Vanessa, the camera lingers on a product-placement fest of ethnic staples, notably omitting Goya products, banished no doubt for their CEO’s endorsement of former President Donald Trump, occasionally interrupted by Sonny, Usnavi’s younger cousin who provides the film’s comic relief and the film’s most viable voice representing a desire for social change .

Yet rather than portraying real resistance to gentrification, the story of “In the Heights” largely presents neighborhood changes as inevitable and promotes the idea that pride in Latino identity is the most important thing to protect. Beauty shop owner Daniela (played by Daphne Rubin-Vega) is sarcastically stoic as she resigns herself to moving her shop far away to the Bronx, declaring she can survive anywhere. Her annoyance about the neighborhood’s indifference to her move sets off one of the film’s most eye-catching set pieces, “Carnaval del Barrio,” a rollicking impromptu dance party in the middle of a blackout that has strong echoes of the “America” scene on a Manhattan rooftop in “West Side Story.”

“Carnaval del Barrio” attempts to create the kind of unified Latino community, at least in New York terms, that many Latino Americans strongly criticized during the 2020 election cycle for being treated as artificially monolithic. Members of the Puerto Rican, Dominican, Mexican and Cuban communities take their turns during the number to wave their national flags, a gesture that may or may not resonate out West or in South Florida.

This display of community, however, seems to take the place of more practical forms of political organizing or awareness. “Maybe this neighborhood is changing forever, Maybe this is our last night together,” Usnavi sings, “Y’all could cry with your head in the sand, I’m a fly this flag that I got in my hand.” While the assertion of pride in a marginalized identity is political by nature, relying solely on identity politics as a vehicle for political expression can shift necessary attention away from social class. In a film as likely to attain stratospheric success as “In The Heights,” the artistic choice to conflate identity with protest feels like a massive opportunity lost.

The underlying mantra that most permeates the film version of “In the Heights” is not about politics or social protest at all, but about the sueñitos, or little dreams, that various characters have — Vanessa’s desire to be a fashion designer, car-service owner Rosario’s dream that his daughter Nina graduate from Stanford, Usnavi’s dream of moving back to the Dominican Republic. These dreams resonate more with the Horatio Alger story Miranda grafted onto Alexander Hamilton; they clash when layered onto the original “In The Heights,” with its critique of out of control real estate developers who create a lack of affordable housing. Instead of overt social protest, “In the Heights” settles for the quiet dignity of a line delivered by Olga Merediz’s Abuela Claudia, about how she survived emigrating from Cuba to New York in 1943: “We had to assert our dignity in small ways, little details that tell the world we are not invisible.”

Sign up for CNN Opinion’s new newsletter.

Join us on Twitter and Facebook

The purported solution to the problems faced by the film’s central characters is the unlikely prospect of winning the state lottery. While the lottery sets off the film’s most impressive musical segment, the hip-hop flavored “96,000,” it provides Usnavi, who inherits the ticket from the suddenly passed-on Abuela Claudia, with cash to hold onto his bodega and stay in the Heights, start a family with Vanessa and pay legal expenses to help Sonny get permanent resident status.

There’s nothing inherently wrong with escapism per se — Latinos, like everyone else, have gone through an unimaginable period of sacrifice, including losing the considerable joys of social gathering. That space of escape — defying gravity, like Benny and Nina do in one climatic scene, dancing up the side of a Washington Heights apartment building — can be crucial to providing a way to gather thoughts and energies for future challenges. Yet it is still disappointing that for a politically and culturally fragmented community still struggling with the devastation of Covid on their communities, widespread housing segregation, and disproportionate exposure to unjust police violence “In the Heights” offers a prescription of singing and dancing, with a social argument coded in quiet dignity and little details that will have to do.

An earlier version of this op-ed wrongly described the background of the character of Nina. Her character is Puerto Rican.

Source: Read Full Article