Is Darjeeling Tea Losing its Fizz?

Scanty rainfall, last year’s lockdown, growing competition from Nepal and the disaster of the 2017 Gorkhaland agitation are steadily weakening exports and sales of Darjeeling tea.

What makes Darjeeling tea a cult brand with a following that ranges from British royalty to Satyajit Ray’s fictional private investigator, Feluda?

A delicate balance of sunshine, rainfall, elevation and the mist that grazes the snow-capped Himalayas.

So if one element plays truant, it can spell disaster.

Scanty rainfall earlier this year dealt a body blow to the season’s first plucking — known as first flush — causing major revenue loss to an industry reeling under sustained misfortune.

The 87-odd gardens in the hills are now staring at a 50 per cent crop loss.

“The first flush makes or breaks Darjeeling. Last year was a disaster (because of the lockdown) and this year we are heading for another,” said Atul Asthana, managing director and CEO, Goodricke Group Ltd, which owns some of the best gardens in Darjeeling including Castleton (that fetched record prices at tea auctions).

“April — the peak for first flush — accounts for 15-20 per cent of the crop and generates around 30 per cent of the entire year’s revenues,” said S Sannigrahi, senior principal scientist, Tea Research Association, Darjeeling Advisory Centre.

Tea Research Association figures show that the crop in April was down 24.73 per cent compared to 2020 and 48.86 per cent compared to 2019.

“In May, the deficit will increase 3-5 per cent because of the after-effect of drought, stress and severe attack of sucking pests like thrips,” said Sannigrahi.

That means that part of the second flush (May-June) is already impacted.

Last year, most of the first flush, which usually fetches premium prices, was lost to the nationwide lockdown to contain the COVID-19 pandemic.

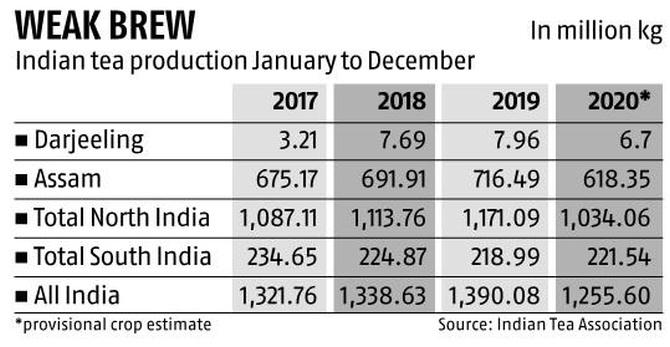

Tea Board numbers show that production from Darjeeling was down by about 16 per cent in 2020 over 2019.

It’s not just Darjeeling that lost crop due to the lockdown.

Estates in West Bengal (Dooars and Darjeeling) and Assam lost about 137 million kg.

Globally, tea production fell 2.2 per cent in calendar 2020, but it was primarily driven by a 10 per cent contraction in India.

With the lockdown, a large part of the population stayed at home, or worked remotely, and guzzled tea.

Even as out-of-home consumption dropped, demand increased and sent tea prices soaring.

Average north India auction prices touched levels not seen in a while.

A report from analysts ICRA said the sharpest increase in prices was for the CTC (crush, tear, curl or machine-processed) variety from North India, which were up Rs 70 a kg (50 per cent), while for south India teas, the average CTC prices increased Rs 44 a kg (46 per cent) in the last fiscal.

But Darjeeling, which produces tea via the orthodox method, did not reap the benefits of this rise.

It was hit on the exports front because it lost the premium first flush. And domestic consumption took a beating, too, because retail shops that deal in loose tea, which account for 70 per cent of Darjeeling tea’s domestic sales, were shut.

Kaushik Das, vice president, ICRA, said average auction prices for Darjeeling in 2020-21 were at Rs 350 a kg compared to approximately Rs 330 a kg in 2019-2020, but lower than Rs 420 a kg in 2018-2019.

The increase in the north India CTC and Assam orthodox showed up in corporate bottomlines.

Das said, an analysis of six or seven listed tea companies showed that the EBITDA margin (earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation and amortisation) increased from 11 to 20 per cent for nine months of FY21 (only some of these companies would have an exposure to Darjeeling and the proportion would be low compared to the rest of the portfolio).

For FY21 as a whole, the EBITDA margin is projected to increase from 4.5 per cent to 13 per cent.

Darjeeling’s cup of woes was full well before the pandemic.

Its problems date back to the Gorkhaland agitation in 2017 that caused the industry to shut down for 104 days between June and September.

“It changed the crop cycle,” pointed out Kaushik Basu, secretary general, Darjeeling Tea Association. “When the estates reopened, the bushes had become trees,” he recalled.

Typically, one-third of the garden is pruned every year. But once they reopened, entire gardens needed pruning.

Production in 2017 fell to 3.21 million kg. About 72 per cent of production was lost in those 104 days, accounting for more than 70 per cent of revenues, said Ashok Lohia, chairman of the Chamong group which produces about 1.1 million kg in Darjeeling and is one of the largest producers of the tea.

So, the famed Darjeeling tea started being substituted. Nepal, which borders Darjeeling, started making inroads.

Indian loose leaf retail shops are its buyers. In the export market, Germany — the largest buyer of Darjeeling tea — consumes it as a ‘Himalayan’ blend.

The EU, UK and the US are major markets; in the EU, Germany has been traditionally the largest buyer.

So much so that a producer said, “The brand Darjeeling was created by Germans.”

Lohia pointed out that about 10 years ago Germany used to import close to 2 million kg; last year, this fell to 1.5 million kg.

What’s more, importers are not willing to pay higher prices.

So, production and exports are falling and prices are not commensurate with the increase in the cost of production (in the last eight years, production has fallen from close to 9 million kg to 6.7 million kg in 2020, exports from 4.14 million kg to 3.10 million kg).

In January, West Bengal announced a Rs 26 a day increase in wages, taking the minimum wage rate to Rs 202 a day for the labour-intensive industry, which pushed up costs even more.

“Hardly any garden is making money in Darjeeling. Gardens are up for sale, but there are no buyers,” said a producer. “It’s like Darjeeling is losing its charm.”

Feature Presentation: Rajesh Alva/Rediff.com

Source: Read Full Article