Modi Sarkar Isn’t Allergic to Privatisation

But use of that word — privatisation — is not encouraged.

This seems to be a classic case of reforms through subtle signals, observes A K Bhattacharya.

A few days before his Independence Day address from the ramparts of Red Fort, Prime Minister Narendra Modi had delivered an important speech at a meeting of leading industrialists, organised by the Confederation of Indian Industry.

Four points stood out as more significant than the rest of his message.

Unfortunately, however, those points have been largely ignored by commentators.

A closer look at them, therefore, would be instructive in the current context of the economic reforms debate in the country.

One, the prime minister sought to redefine his idea of Make in India.

He clarified that making in India did not mean made by Indians.

He did not elaborate further on the subtle distinction that was inherent in that clarification.

But his statement in the context of his championing of an Aatmanirbhar Bharat (self-reliant India) was a clear signal: ‘Today, the sentiment of the countrymen is with the products made in India. It is not necessary that the company is Indian, but today every Indian wants to adopt products made in India.’

The implication for the Indian industry was even more significant.

He asked industry to ‘make its policy and strategy accordingly’, so that it can move forward in the Aatmanirbhar Bharat campaign.

Two, the prime minister chose to dispel all impressions in the minds of industry that his government was suspicious of foreign investment.

Riding on a steady flow of foreign investment of different types, the government of Modi seemed to show no hesitation in welcoming foreign investment to help meet its resources need for economic development and execution of new projects.

And the indication was that the government would not shy away from necessary steps if the need of the hour was to amend laws that might spoil the mood of foreign investors.

‘India, which was once apprehensive of foreign investment, is welcoming all kinds of investment now. India, whose tax policies once used to cause disappointment among investors, now has the world’s most competitive corporate tax and faceless tax system,’ he said, while gently hinting at the recent lowering of corporation tax rates and removal of the retrospective provisions in the application of the 2012 tax on capital gains.

Three, the prime minister reiterated his government’s commitment to simplifying laws and rules that had for many years strangled the industry’s enterprise and initiative.

He referred to the exercise recently undertaken to simplify and consolidate as many as 29 different central labour laws into four labour codes.

Raising labour law reforms in an industry meeting is understandable.

But explaining to industry the significance of his government’s recent initiative to reform three agriculture-related laws was unusual, given the nature of the criticism those reforms had triggered.

‘Where once agriculture was considered only as a means of subsistence, efforts are being made now to directly connect Indian farmers with the markets of the country and abroad through historic reforms in agriculture,’ he said.

And four, the prime minister told the industry leaders that decisions were being ‘taken through the new public sector enterprises policy to rationalise and minimise the footprints of the public sector’ and urged industry to ‘exhibit maximum enthusiasm and energy from its side’. This was yet another signal to the Indian industry.

In sum, the four messages constitute a slightly more nuanced approach of the Modi government to economic reforms or, more appropriately, economic policy-making.

Make in India is certainly part of the Aatmanirbhar Bharat campaign, but this does not preclude a vibrant and growing role of foreign capital.

Indeed, the Make in India policy will include all projects even when they are floated by foreign capital or foreign companies.

The key condition is such goods should be manufactured within the country.

It is perhaps this obsession with manufacturing within the borders of India that has encouraged the government to raise tariffs.

The idea is to provide protection or the so-called level playing field to investors in a domestic manufacturing project.

It is a different matter that such a tariff-based approach does not yield sustainable benefits either for the economy or consumers as this over time would undermine their intrinsic competitiveness and exports capability.

It is important to note that the government’s welcome to foreign investment with open arms is only for the manufacturing sector through the Make in India campaign.

Foreign investment in the services sector or e-commerce companies does not enjoy the same privilege.

This seems to be the new deal that the government is offering to the Indian industry.

This new deal comes along with the promise of labour law reforms and the new agricultural laws that would allow the Indian corporate sector to build linkages with the farm sector.

Both labour law and agricultural law changes have become contentious.

Rules for the four labour codes are yet to be framed.

The new labour minister is holding consultation with representatives of the major national trade unions and is even open to reviving the Indian Labour Conference, an annual tripartite conference of the government, employers and employees, to resolve the contentious issues.

Similarly, urging Indian industry to view the agricultural reforms, which at present remain suspended, as an opportunity for expanding their business linkages is a clear sign that the Modi government is keen on reviving those laws.

Otherwise, it does not make sense for the prime minister to talk about agricultural reforms in an industry body meeting.

A new compact on reforms appears to be evolving between the Modi government and the Indian industry.

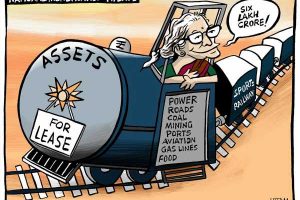

What about the PSE policy? Note the careful usage of words.

Modi talks about a PSE policy that would rationalise and minimise the footprint of the public sector.

There is no mention of privatisation. The last time the finance minister talked about privatisation was in her Budget speech in February 2021.

Even while securing Parliament’s approval of the Bill to effectively allow the government to privatise State-owned general insurance companies, the finance minister’s clarification was intriguing: ‘It is not to privatise, we are certainly bringing some enabling provision so that citizens can have some participation. Our market can give the money from retail funds, through Indian citizens…The public participation is only going to help us by bringing more resources.’

Remember that the General Insurance Business (Nationalisation) Amendment Bill, 2021, sought to remove the requirement that the Centre should hold not less than 51 per cent of the equity capital in the four State-owned general insurance companies.

That seems to be yet another new and important message.

The Modi government is not averse to privatisation. But the use of that word is not encouraged any more.

This seems to be a classic case of reforms and policy-making through subtle signals.

Many years ago, Indira Gandhi’s principal secretary, P N Haksar, had said that growth and reforms had to be delivered in India by stealth.

Under the Modi regime, shifts in policy and reforms may happen through subtle signals.

Feature Presentation: Rajesh Alva/Rediff.com

Source: Read Full Article