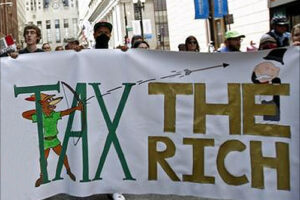

Taxing The Rich To Please The Poor

Taxing the rich will fetch nothing; only votes, argues Debashis Basu.

Recently, Bloomberg reported India was preparing to overhaul its direct tax laws to help ‘Prime Minister Narendra Modi reduce widening income inequality’.

Already, in the recent Budget, the government decided to tax debt funds at the normal income-tax rate. When the article appeared, there was consternation among a few, leading the government to backtrack immediately. But the genie was out of the bottle. The government had prepared us.

It is now a matter of time before long that capital gains tax rates will be ‘rationalised’. But will taxing the rich reduce inequality when the rich are getting richer not due to tax advantages but due to mind-boggling corruption, opaque rules, regulatory failures, weak institutions, and gaming the system at all levels?

It could well be we need to tinker with tax rates but that should be the least of our priorities if we want to fix income inequality.

In a parliamentary question on December 21, the government disclosed the revenue it earned from long-term capital gains (LTCG) for the assessment year 2020-2021 was just Rs 5,311 crore (Rs 53.11 billion).

The money raised through a higher capital gains tax will hardly add much to the Rs 24.4 trillion of revenue receipts and Rs 41.9 trillion of spending estimated for 2023-24.

It also pales in comparison with the enormous resources wasted across central and state governments through ineffective schemes and plain old corruption, which has continued unabated.

Remember also that 31 per cent of government receipts go into paying interest and salaries. But nothing can be done about these two expenses.

So, tinkering with LTCG tax cannot yield much money to make any difference. Perhaps the government is looking for a ‘garibi hatao‘ type of message to win votes in the next general elections, which are a year away.

A higher capital gains tax serves to burnish the government’s image as pro-poor and show the rich their right place.

It will be like the magic of demonetisation, which did not reduce income inequality, root out corruption, or teach the rich any lessons. But it was enthusiastically supported by otherwise economically intelligent and literate people through clever slogans, memes, and anecdotes.

If the Bloomberg report was a trial balloon, which the finance ministry was quick to shoot down, it shows that the Modi regime is circumspect about how the ‘rich’ will react to being taxed more for their capital gains. It need not fear.

Not only have Indians displayed an enormous capacity to suffer pain and discomfort — whether in their daily lives or through sudden shocks like demonetisation — the majority of the people in the capital markets remain convinced that all problems are temporary and India is confidently marching towards being an economic superpower, a $5 trillion economy.

There is, however, one flaw in their understanding: India cannot become an economic superpower, or reduce income inequality, in the absence of strong institutions. And we do not have those.

To become prosperous (forget about becoming an economic superpower) and achieve lower income inequality, strong economic growth is essential but not adequate. That growth needs to be sustained for a long time, supported by low inflation and low interest rates.

This is possible only when the economy can adapt to shocks, which in turn is possible only through responsive rules, systems, and strong institutions. Otherwise, growth will stall and a majority of the people will not benefit from the sporadic high growth periods.

This is not a conjecture but learning from history. This is exactly what happened during previous periods of high growth in the mid-1980s, mid-1990s, mid-2000s, and again in 2010-2012. Each of these phases produced a few years of superficial, headline-grabbing, high growth, which quickly fizzled out without reducing income inequality.

The growth spurt of the mid-1080s pushed India to the brink of default, at one time leaving India with foreign exchange worth less than two weeks of imports.

The growth of the mid-1990s immediately generated high interest rates and inflation, which punctured the euphoria of liberalisation.

The growth in 2003-2007 was more solid, but the global financial crisis exposed our fundamental weaknesses.

The 2010-2012 growth phase, goosed up through easy money, brought upon us higher inflation and higher interest rates, leading to a foreign exchange crisis in mid-2013.

There is a simple reason why such high growth periods have been unsustainable.

The moment growth picks up, businessmen turn bullish. Their actions set off a chain of higher demand growth. Accelerating demand and sensing a bullish financial outlook, financial markets go euphoric, leading to irrational capital allocation.

But an institutionally weak economy, full of hidden frictional costs, cannot handle the demands of such high growth and sudden capital rush.

Supply takes a long time to catch up. If supply does not come up fast enough, strong demand growth fuels inflation, which has to be curbed with higher interest rates. From boom, we inevitably go to bust.

Only an economy that can quickly respond to higher demand by keeping inflation and interest rates moderate, while ensuring continued growth, will slowly succeed in spreading prosperity and reducing income inequality all around.

This calls for highly adaptive and responsive institutions and regulatory systems.

For example, in a boom, there will be a higher demand for hotel rooms. Can hoteliers add to the supply quickly enough? Not with scores of state and central permits that take years to be cleared.

It is the same for every industry. Unfortunately, no government has done much to make our regulations fair and transparent, and our institutions accountable.

Their actions have been quite the opposite — arbitrary, unfair, and unaccountable. Corruption is endemic.

As long as all this remains, income inequality will keep widening and taxing the rich will fetch nothing; only votes.

Debashis Basu is editor of www.moneylife.in and a trustee of the Moneylife Foundation.

Source: Read Full Article