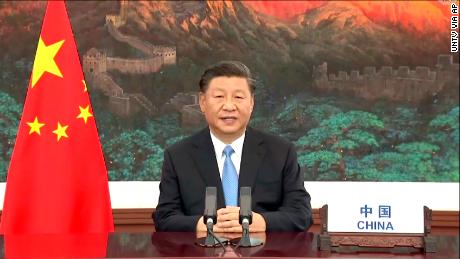

Xi Jinping pledges to make China carbon neutral by 2060

Hong Kong (CNN Business)There’s no solution to the climate crisis without China. President Xi Jinping just gave hope it might deliver one.

But his pledge to make his country carbon neutral within 40 years — delivered late last month at the United Nations — will require nothing short of a revolution for the world’s biggest polluter.

The problem is that China’s vast economy just isn’t built for a dramatic pivot to green policy. It spent decades staking its ascent on massive infrastructure projects and manufacturing, building an economic engine that is now heavily reliant on dirty energy.

The country burns billions of tons of coal each year and uses hundreds of millions of barrels of oil — and analysts say that economic pressures caused by Covid-19 and tensions with the West are pushing China to spend more on those energy sources, not less. And while the Chinese government has enacted policies meant to curb emissions, research has shown that they haven’t really moved the needle.

While carbon emissions fell after China’s unprecedented coronavirus lockdown earlier this year, pollution had already rebounded by late spring, according to an analysis from Lauri Myllyvirta, lead analyst Centre for Research on Energy and Clean Air (CREA), an environmental organization.

China remains the largest car market on the planet and the industry still leans heavily on gasoline and diesel-powered vehicles. Beijing has set lofty targets to promote the development and use of electric cars, but their market share remains scant.

“China’s announcement to strive for carbon free within the next four decades is an unprecedented move,” said Li Shuo, a climate and energy policy adviser for Greenpeace East Asia. “To achieve the vision would imply massive re-arrangement of the Chinese economy.”

An economy reliant on coal and oil

Coal is still China’s primary energy source by a long shot, accounting for 58% of the country’s energy demand, according to the National Bureau of Statistics. China burned about four billion tons of coal last year, making it the largest consumer in the world.

Add crude oil into the mix — China produces or imports hundreds of millions of barrels each year — and the two fuel sources account for a combined 77% of China’s energy use. Natural gas, wind, nuclear and hydro power made up the rest.

China has promised repeatedly to kick its coal habit, and the government has for years touted policies intended to clean up its act. It has, for example, required that methane from coal mining be captured or converted into carbon dioxide, which is less potent.

But the reality doesn’t match the rhetoric. A study released in the journal Nature last year showed a steady growth in China’s methane emissions. And energy-related carbon emissions in China last year were 80% higher than they were in 2005, according to the International Energy Agency.

There’s also plenty of evidence that China has continued to invest in coal and oil, particularly as the coronavirus pandemic and tensions with the United States threaten economic growth. While research has shown that building and investing in renewable energy can be cheaper than coal, the latter remains heavily subsidized by the Chinese government and is a big employer in the country.

This year alone, eight provinces using the most energy in China, including Guangdong and Jiangsu, have directed 600 billion yuan ($90 billion) toward projects that use coal for chemical production, according to CREA, the environmental organization.

CREA also noted the eight provinces are planning to spend a combined 420 billion yuan ($62 billion) on oil refinery projects this year as China tries to reduce its reliance on foreign oil. Some 70% of the country’s crude oil supply is imported.

The spending on clean energy is small by comparison. All told, CREA said that the provinces are directing more than $300 billion toward projects that involve fossil fuels — about three times as much money as they are putting toward initiatives to promote electric vehicles and low-carbon energy projects.

The average amount that local governments are spending on clean energy “is so small that they are dwarfed by the spending plans for a few oil refineries alone,” Myllyvirta, the CREA analyst, wrote in a report released last month. He added that while China has said it would invest more in new infrastructure such as 5G and blockchain projects, that emphasis is “is not evident in the spending priorities we identified.”

Myllyvirta told CNN Business that phasing out fossil fuels will be China’s main challenge, adding that the industry is largely state-owned and “politically powerful.”

The largest car market

China has been the world’s largest car market for more than a decade. But cars are notorious for their contributions to environmental damage, and auto emissions are a major source of air pollution in Chinese cities, according to China’s Ministry of Ecology and Environment.

Beijing has been trying for years to boost the popularity of electric cars, which are considered key to meeting any target to reduce carbon emissions. Xi’s government wants new energy vehicles, such as electric or plug-in hybrid cars, to make up a quarter of its auto sales by 2025.

The government has imposed strict emission standards on vehicles that are sold in the country, and offered tax breaks and cash incentives to manufacturers and customers as a way to encourage them to make and purchase more electric cars.

There has been some progress. Electric vehicles now comprise 5% of the market, compared to just over 1% five years ago, according to the China Association of Automobile Manufacturers. But that still means more than 20 million new polluting vehicles hit China’s streets last year.

Myllyvirta said there’s reason to be optimistic about China hitting its sales targets, though. He pointed out that even after the country slashed subsidies for electric cars last year, market share for the vehicles isn’t slipping — a sign of progress.

But the government still “needs to go little faster” in expanding how much of the market electric cars can capture, according to Richard Black, director of the Energy and Climate Intelligence Unit (ECIU), a UK-based climate activism and advisory organization.

“It won’t happen by itself,” Black said. “The government will need to continue with the many measures it has to stimulate both supply and demand.”

Future climate goals

Beijing has aggressively defended its climate policies. Last month, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs blasted a recent report from the US State Department accusing China of environmental abuse. Washington argued that Beijing’s greenhouse emissions are still rising at a quicker pace than global emissions.

“This is another anti-China farce staged by the US for political purposes,” spokesman Wang Wenbin told reporters. “China’s achievements in tackling climate change are obvious to all.” He said the country’s carbon dioxide emissions as a unit of GDP have fallen nearly 50% since 2005, and that non-fossil fuel energy now makes up 15% of what the country uses — exceeding its targets for 2020.

It’s true that China is promoting some positive climate policies, according to the Climate Action Tracker (CAT), a Berlin-based organization that tracks government action. The group lauded China for remaining committed to renewable energy and electric cars, for example.

But CAT warned that the activities fueling China’s economic recovery are still largely carbon intensive. And investment in the country’s dirtiest energy projects doesn’t appear to be fading anytime soon.

“Most worryingly, China remains committed to supporting the coal industry while the rest of the world experiences a decline,” CAT said, adding that the country “is now home to half of the world’s coal capacity.”

After lifting a ban on constructing new coal plants in 2018, the group said, China continued to ease restrictions on coal. CAT added that by the middle of 2020, the country had allowed more new coal plant capacity than in the last two years combined.

Xi’s carbon neutral announcement last week was light on detail, offering little clarity on just how aggressive — or not — China is planning to be if it hopes to reach its targets.

But Myllyvirta noted that even just the tone from the top could help, as long as there is follow-through.

“The significance of the [Xi] announcement is precisely in the potential for shifting the energy, emissions and investment trends that have been shifting in a concerning direction in the past few years,” Myllyvirta said, adding that a “major new policy target” introduced by Xi “can and should prompt reassessment of policies and investment priorities.”

— Helen Regan contributed to this report.

Source: Read Full Article