There is a serial forger in Kleiman vs Wright, and it isn’t Satoshi

For months and even years in the lead-up to Kleiman v Wright, the idea that there are forged exhibits in “evidence” has come up often.

Usually, it comes up in the form of indignant bleating from the people who have already decided (or been paid to decide) that Dr. Craig Wright couldn’t possibly be behind the Satoshi Nakamoto pseudonym. After all, if you can get enough people to write a person off as a serial forger, you can make sure they are never taken seriously again.

That is perhaps the reason for the seemingly immortal claim that if there are any forgeries connected to Wright, it must be Wright who is responsible for them. Who else would have the motive to alter and forge documents? Right?

However, as the Kleiman trial began and as thousands of pages of evidence and hours of testimony were presented to the jury, it has become apparent that this assumption is way off, and that though there is a serial forger in the midst of the Kleiman v Wright suit, it isn’t Wright.

Vital forgeries which can’t be blamed on Wright

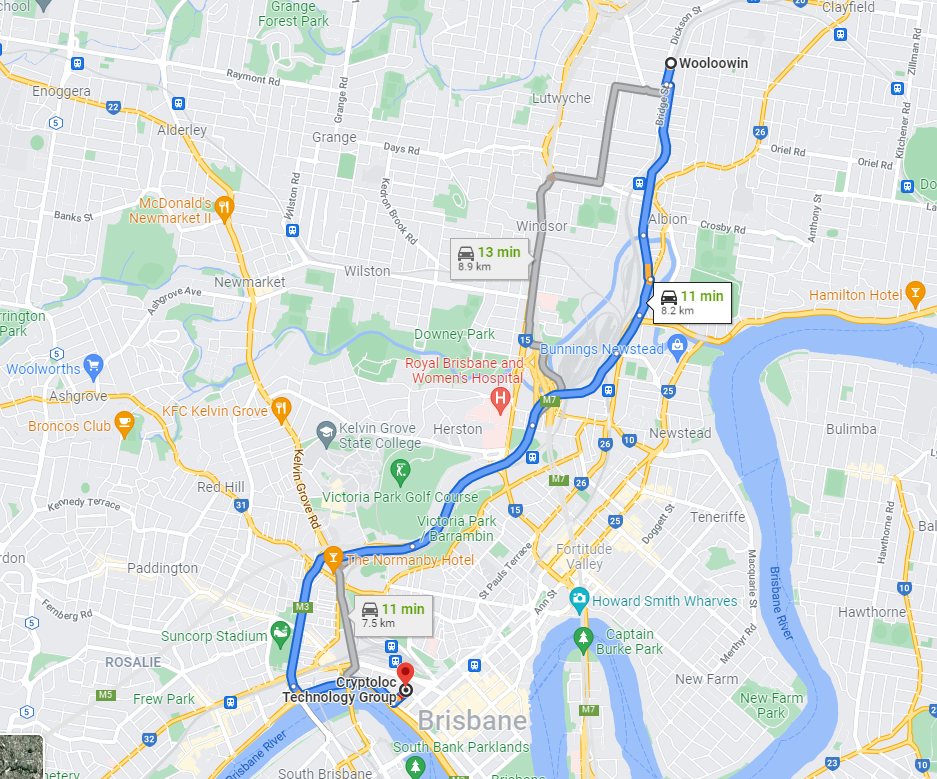

To those paying close attention to the case, this won’t be a huge surprise at this stage. Expert witness Dr. Matthew Edman testified for the plaintiffs that 40 or so emails he reviewed had been forged: specifically, he was able to determine that IP addresses associated with some of the forgeries came from Wooloowin, a suburb of Brisbane Australia.

At the time the forgeries were said to have been created, Dr. Wright was living and working in Sydney, 900km and a 9.5-hour drive from Wooloowin—suggesting whoever has been forging evidence, it isn’t Dr. Wright.

Wright was further exonerated when he returned to the stand on Monday and was presented with an email—P2 on the plaintiff’s exhibit list—purportedly sent from Wright to Dave Kleiman on March 12, 2008:

I need your help editing a paper I am going to release [sic] later this year. I have been working on a new form of electronic money. Bit cash, Bitcoin…

You are always there for me Dave. I want you to be a part of it all.

I cannot release it as me. GMX, vistomail and Tor. I need your help and I need a version of me to make this work that is better than me.

This email was introduced by the plaintiffs and is vital to their case against Wright because it is the only primary evidence that indicates Dave had any involvement in the Satoshi Nakamoto partnership at all. Wright has always indicated that Dave Kleiman helped edit the white paper, so the email isn’t a slam dunk for the plaintiffs, but it does a lot of heavy lifting for the plaintiff’s case. Without this email, there is zero evidence that Dave and Wright ever talked about Bitcoin before it was released publicly.

What is important is that the email comes from one of Wright’s well-known domains (@rcbjr.org). But public records show that the domain wasn’t registered until 2011 (something which Wright confirmed on the stand). Further, the metadata analysis produced by the defense show that the email was sent in 2015, rather than 2008.

In other words, the 2008 email seems to be at least partly inauthentic.

It should be mentioned that this particular email was conspicuously left off the list of documents sent to Edman by the plaintiff’s lawyers for analysis. Given its importance to the plaintiff’s case and what we now know about the email, it would seem that this omission was deliberate.

However, the most intriguing bit of evidence showing that the email is a forgery has nothing to do with metadata. In something of a ‘gotcha’ moment at the expense of the plaintiffs, Dr. Wright explained to the jury that the @rcjbr.org domain refers to the initials of his family: Ramona, Craig, and his three kids first initials J,B and R. Given that Wright didn’t meet his wife until 2010, the email couldn’t have been sent prior to that even ignoring the metadata.

This puts the 2008 email in a category of its own among the allegedly forged evidence in the case, because it’s the only one where we can definitively rule out any suspects. Whoever forged this document can’t have known what @rcjbr.org stands for, and the email itself is only detrimental to Wright’s defense—which means whoever did the forging was almost certainly someone other than Wright.

In addition to exonerating Wright, it also lends credence to his long-standing claims that some of the evidence being relied upon by the plaintiffs—such as the Australian Taxation Office (ATO) documents—have been forged.

But by who?

Not Dr. Wright

The first thing to clarify is that contrary to what Wright’s detractors would have you believe, the plaintiffs have not been the only party to complain about forgeries on the docket. In fact, it has been the plaintiffs who have fought the hardest to keep the evidence of bogus documents from being considered by the jury.

For example, Dr. Wright’s legal team had expended considerable effort before trial to make sure the issue of forged evidence was put before the jury. They fought to have an expert presented at trial who would testify that certain documents on the record contained forged signatures—including that of Wright. The plaintiffs successfully argued to have the expert excluded.

Consistent with this strategy, the plaintiffs went even further, filing a motion to get the court to prohibit Wright from claiming that any documents in the case had been forged. The court rejected this out of hand on the basis that any claims of forgeries are for the jury to evaluate.

So, even going into the trial, the idea that the record was littered with documents and emails forged by Dr. Wright didn’t make sense. Add to that the fact that the most definitive thing anyone can say about any of the apparent forgeries on the record relates to the 2008 RCBJR email: that whoever made that forgery, it could not have been Dr. Wright.

As the person with hundreds of billions to gain from demonstrating that Dr. Wright was both his brother’s business partner and a compulsive liar, Ira Kleiman is an obvious candidate. The aforementioned pre-trial strategy of preventing Wright from complaining about forgeries certainly indicates that the plaintiffs were well aware that some of their evidence are of questionable authenticity.

Ira isn’t much of a computer expert, however, so if he was forging documents, he at the very least was using someone else to do it.

Jamie Wilson had means, motive and opportunity

There is another suspect worth considering: Jamie Wilson, witness in Kleiman v Wright and former CFO to Dr. Wright.

Remember the testimony by Dr. Edman, presented as part of the plaintiff’s case, which revealed that at least some forgeries were done by an IP based in Wooloowin, Brisbane? Wilson’s company, Cryptoloc, is just an 11-minute drive from Wooloowin.

Further, though a former accountant, Wilson is technologically competent: he runs a successful cryptographic security company, Cryptoloc, so it’s fair to say his competency to create convincing digital forgeries exceeds that of Ira Kleiman.

All of this is circumstantially damning by itself, but a close look into the relationship between Dr. Wright and Jamie Wilson reveals that Wilson had plenty of motivation to implicate Wright in what is said to be most valuable robbery in history.

Jamie Wilson is Dr. Wright’s old chief financial officer, and his testimony formed a curious part of the plaintiff’s case: he appeared to be brought on to opine about the quality of Wright’s various company books, but admitted under oath he’d never seen them in more than a year he supposedly spent serving as CFO. He complained he was never paid for his work with Dr. Wright, but then admitted under oath that no one had ever agreed to pay him in the first place.

Maybe most importantly, Wilson testified that he quit in 2013, while Dr. Wright testified that Wilson was fired. Wright’s story is at least backed up by writings from as early as 2020, where he mentions that around the time Wilson exited the business, he was caught trying to steal and sell Wright’s intellectual property.

That’s right: the person who lives and works just 11 minutes from the suburb proven to be the location where the much-discussed forgeries took place was fired by Wright years ago for stealing intellectual property.

Perhaps more relevant to the question of the forgeries is the fact that the patent which sits at the heart of Wilson’s Cryptoloc business bears Dr. Wright’s name. In fact, Wilson is attached to multiple applications relating to the same Cryptoloc patent, and every one of them—even those filed as late as 2017, well after Wilson had been fired by Wright—bear Wright’s name.

This would seem at odds with answers Wilson gave in his Kleiman v Wright deposition. There, rather than conceding that Dr. Wright (who according to Wilson, was sought out specifically for his expertise in cryptography) played any role in his patents, he began claiming the opposite: that Dr. Wright was on the patents in name only and hadn’t contributed to them at all.

That’s a highly convenient state of affairs for Wilson, because he would go on to leverage the patent originating from his time with Wright to launch Cryptoloc. It turns out that Wilson’s company was listed as one of the 20 Best Cybersecurity Start Ups to Watch in 2020 by Forbes. In the Forbes piece it mentions how the company has set up a new Regional Headquarters for Europe in Cambridge, England. Right in Dr. Wright’s back yard. Certainly, the last thing Wilson or his lucrative business needs is to be accused of stealing from one of the most celebrated inventors in modern history.

Wilson also had more opportunity than anyone to plant damning and convincing forgeries in a way that would implicate Dr. Wright. He had been working in Wright’s companies since 2012, well after Bitcoin had been released to the world, so he would have had a front-row seat to the inner workings of the Wright machine during the elusive time period which is the focus of the Kleiman lawsuit. He also testified that Wright told him about Dave when the two worked together, and Wilson’s involvement with Wright’s companies also coincided with Wright’s ongoing skirmish with the ATO about the tax position of Bitcoin, long before he was outed as Satoshi.

Wilson’s knowledge of the Wright’s fight with the ATO makes him particularly unique as a suspect because it is the ATO documents in evidence in Kleiman v Wright that are perhaps of the most questionable authenticity. Wright’s attorneys fought hard to have these documents thrown out before trial on the basis that they could not be authenticated. Indeed, the pages of ATO documents, which relate to audits of Dr. Wright’s companies which are not parties to this lawsuit, contain unsworn statements, interview transcripts without any seal of authenticity, and documents which are outright incomplete. The motion was denied on the basis that the deficiencies raised by Wright don’t rise to the standard required to have the evidence tossed, but the problem reared its head at trial when the plaintiffs attempted to make sense of the documents in front of the jury. Wright repeated his claim that the ATO documents are incomplete and unverifiable, and the plaintiff’s attorneys could say nothing in response, no doubt leaving the jury wondering why they’d bothered in the first place.

Even ignoring the shortcomings within the ATO documents themselves, their origin is so dubious that they are evidentiarily useless. The story goes that Ira was contacted by the ATO’s “criminal investigations unit,” and that’s how he came to be in possession of the documents. The story itself is highly questionable: there is no criminal investigations unit within the ATO, and the plaintiff has never tried to introduce testimony from anybody at the ATO who might be able to testify to their accuracy.

Even if there was, in a criminal investigation the chain of custody is everything. Access to evidence is closely monitored and documented so that any changes or discrepancies are obvious and can be challenged by the defendant. Here in civil proceedings, the burden is much lower, which means that the ATO evidence is as good as a bundle of documents handed to Ira by a stranger on the street. Wright (and therefore the jury) can only take them at face value and have no way of knowing what happened to the documents from the time it (supposedly) left the ATO’s inbox in Australia and ended up in discovery in this case. But from the point of view of somebody trying to denigrate Dr. Wright, getting the ATO documents admitted is nothing short of a luxury—because assuming someone had the means to do it, they could have made any amendments or additions they wanted prior to it being sent to Wright’s lawyers and it still would have ended up in Kleiman v Wright as evidence for the plaintiffs.

In other words, Wilson is one of the only people in the world who could have known all the ingredients necessary to successfully implicate Dr. Wright in the robbery of a partnership which never existed. What’s more, Wilson at best had a bone to pick with Dr. Wright after being unceremoniously let go, and at worst saw Wright as a loose end which could potentially unravel the business he’d built atop their shared patent.

The real question would be how Wilson could possibly have known his breadcrumbs would eventually lead to Dave Kleiman’s brother suing Wright for hundreds of billions of dollars, particularly when for all he knew Wright’s identity would remain a secret forever.

Of course, Wilson doesn’t need to have expected his trail of forgeries would be quite so spectacularly effective, nor does he need to have acted alone. Some of the forgeries were determined to have originated in 2015, for example, after Ira Kleiman had started sniffing around for Wright’s Bitcoin. Wilson may have left a trail of evidence leading Kleiman to Wright, but he could just of easily have collaborated with Kleiman directly in building a case against Wright.

The fact does remain, however, that any attempt to frame Wright for bilking his best friend out of his share of the Satoshi Nakamoto partnership would be futile if no one ever found out that Wright was involved in the creation of Bitcoin.

On this, harken back to the debunked email from March 2008, which has the effect of both confirming Wright to be Satoshi and implicating Dave as a partner. It turns out the Kleiman v Wright lawsuit is not the first time that email has been seen by the general public: it was one of the key pieces of evidence leaked to Wired and Gizmodo which caused them to expose Wright in 2015. That email, together with evidence which included the dubious ATO documents, formed the basis of Wired and Gizmodo’s story—if those outlets didn’t receive these documents from someone, they likely don’t run the story.

No one knows who leaked Wright’s identity to Wired and Gizmodo. It makes no sense for it to be Wright: the breaking of the Gizmodo and Wired story was accompanied by the Australian Federal Police raiding his home, and we can see from private emails between Wright and colleagues that he was just as surprised by the reporters sniffing around before they published their story as the rest of the world was when it was released.

We also know from evidence shown at the Kleiman v Wright trial that Gizmodo was communicating with Ira Kleiman via one of Dave’s many old email addresses, which seems to definitively disprove the idea that the Gizmodo journalists discovered and printed the Wright story without being tipped off by someone familiar with Wright and Dave Kleiman? How else would it be possible for the journalists investigating the Satoshi Nakamoto story to get a hold of Dave’s old e-mail address, and most importantly, how could they have possibly known it was an address that could be used to get in touch with his brother Ira?

Similarly, Ira swore the ATO reached out to him directly, apparently via old inboxes that also belonged to Dave. How did the ATO get these addresses of Dave? And how could they have possibly known Ira Kleiman would be the man on the other end of the line? And how did they vet Ira was really Dave’s brother before sending him the ATO documents? Dr Wright himself testified that he no idea that Dave had a living brother, so how did they come to send pages of documents allegedly from their own investigations to an inbox that was—by all accounts—totally unidentified?

Given that we now know that at least part of what Wired and Gizmodo received were forgeries, some of which have been shown to have originated not 20 minutes’ walk from Wilson’s place of business, and given that we know that whoever was talking to both those publications and the ATO was someone very familiar with Wright and the Kleimans, perhaps we can take a good guess at who was involved.

Check out all of the CoinGeek special reports on the Kleiman v Wright YouTube playlist.

Source: Read Full Article