The US has radically changed how it deals with economic turmoil

American political leaders have learned a few things in the past 12 years, since the nation was last trying to claw its way out of an economic hole.

Among them: People like having money. Congress has the power to give it to them. In an economic crisis, budget deficits don’t have to be scary. And it is better for both the economy and the democratic legitimacy of the effort when elected leaders choose to help people by spending money, versus when pointy-headed technocrats help by obscure interventions in financial markets.

Far from leaving it up to the Fed, US leaders have become increasingly used to using their power to supercharge the economy.Credit:Stephen Kiprillis

Lawmakers rarely phrase things so bluntly, but those are the implications of a pivot in US economic policy over the past year, culminating with the Biden administration’ $US1.9 trillion ($2.5 trillion) pandemic relief bill. It is set to pass the House within days and be signed by President Joe Biden soon after. And while this vote will fall along partisan lines, stimulus bills with similar goals passed with bipartisan support last year.

Leaders of both parties have become more willing to use their power to extract the nation from economic crisis, taking a primary role for managing the ups and downs of the economy that they ceded for much of the past four decades, most notably in the period after the 2008 global financial crisis.

It is an implicit rejection of an era in which the Federal Reserve was the main actor in trying to stabilise the nation’s economy. Now, elected officials are embracing the government’s ability to borrow and spend — the “great fiscal power of the United States” as Jerome Powell, the Federal Reserve chair, has called it — as the primary tool to fight a crisis.

“That’s really been the story of this recovery,” Powell said at a recent hearing. “Fiscal policy has really stepped up.”

The new relief bill is similarly a rejection of the concerns of centrist economists, including former Treasury Secretary Larry Summers and former IMF chief economist Olivier Blanchard, that the size and structure of the new legislation invites inflation or other problems. Democratic lawmakers have concluded that the favourable politics of this plan outweigh such risks.

If sustained, this assertion of control over economic management by elected leaders would be as momentous a change as the one that followed the Paul Volcker Fed in the 1980s.

“This is an enduring regime shift,” said Paul McCulley, who teaches at Georgetown University’s McDonough School of Business. “Having the tools of economic stabilisation work a whole lot more through the fiscal channel and a whole lot less through the monetary channel is a profound, pro-democracy policy mix.”

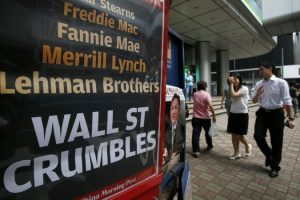

It is in distinct contrast with the experience after the 2008 financial crisis.

“We’re at a watershed moment where this type of tool will be used in future recessions”

There was a large 2009 fiscal stimulus action, but a mix of legislative politics and deficit concerns by some officials in President Barack Obama’s inner circle reined in its size. Many of its components were relatively invisible to the average voter. And when the economy remained weak into 2009 and 2010, Republicans and many Democrats focused on deficit reduction.

“Stimulus” became a dirty word in Washington.

The Fed stepped in, undertaking quantitative easing (essentially, buying bonds with newly created money) and other untested strategies in an effort to keep the expansion going.

But central bankers’ tools are limited. They can adjust interest rates and push money into the financial system in hope of making credit easier to obtain. That can spur more investment and spending, which in turn can generate more jobs and higher wages.

Sound circuitous? It is — the economics equivalent of a triple bank shot in billiards.

The US relied on the Fed to stimulate the economy after the GFC, but times have changed.Credit:AP

In the 2010s, the strategy sort of worked. There was no dip back into recession, and the expansion was the longest on record, until the pandemic ended it. But it took years and years for the economy to return to health, and it was a deeply unequal recovery in which owners of financial assets saw the biggest gains. That the effort was led by unelected central bankers reduced its democratic legitimacy, by appearing as if it was merely an effort by elitist institutions to protect the rich and powerful at the expense of everyone else.

“You can do it and it can be successful, but the income and wealth inequality consequences of it will stink to high heaven,” McCulley said. “You can do it that way, but it is anathema to democratic inclusion.”

By contrast, fiscal authorities can spend money directly, funnelling it where it is needed, without expectation of being paid back. The United States has done exactly that over the past year on a scale with no parallel since World War II.

The new $US1.9 trillion package includes, among other provisions, $US1400 payments to most Americans, a new child care tax credit that will put $US300 per month in the bank accounts of most parents of a young child, help for those facing eviction or foreclosure, and billions of dollars in grants for small businesses. Public opinion polling finds it considerably more popular than other major domestic policy legislation in recent years.

Republicans unanimously opposed the Biden legislation, but it has not been quite the scorched-earth opposition to deficit-widening action seen during the Obama administration.

As evidenced by previous rounds of pandemic relief, there has been enough common ground between Democrats and Republicans to reach bipartisan agreements of relatively large scale, including the $US2 trillion CARES Act enacted in March 2020.

“A relief package like this one might not have been everything both parties wanted, but a compromise deal that provides help to Americans is better than no deal at all,” Representative Tom Cole said at the outset of the House debate on a $US900 billion bipartisan bill in late December.

“Fiscal policy has stepped up.” US Federal Reserve chairman Jerome Powell.Credit:AP

All in all, Congress and the Trump and Biden administrations have authorised about $US6 trillion in pandemic relief spending over the past year, about 28 per cent of 2019 GDP. (Less than that will have ultimately been spent, because the economy’s improvement has left some programs with more money allocated than they needed.)

“We’re at a watershed moment where this type of tool will be used in future recessions,” said Constance Hunter, chief economist of global accounting firm KPMG. “What we did here is different and unique, and we are going to learn whether it was effective at providing a bridge to the other side of the pandemic.”

There are risks in the Biden administration’s approach, of course. If the concerns described by Summers and Blanchard about the size of the new relief bill materialise, and the result is excessive inflation or some type of crisis, then Democrats will pay a price for their actions.

But that’s the thing about democracy: It has much clearer mechanisms for holding elected officials accountable for their economic policy decisions than it does appointed experts for their interest rate policies. If Americans don’t like the results, they have a straightforward way to make it known: at the ballot box in November 2022 and November 2024.

The New York Times

Business Briefing

Start the day with major stories, exclusive coverage and expert opinion from our leading business journalists delivered to your inbox. Sign up for the Herald‘s here and The Age‘s here.

Most Viewed in Business

From our partners

Source: Read Full Article