Congress can talk a lot about Ukraine, but its power to act is limited

John Kirby reveals the Pentagon’s mission in Ukraine

Pentagon press secretary provides insight on response to the Russia-Ukraine conflict on ‘The Story.’

Congress is trying to do something about Ukraine.

Only, it can’t do much.

There are increasing calls — especially among Republican lawmakers — for NATO to impose a no-fly zone in Ukraine.

A war spilling over into Europe alarms many on Capitol Hill. That’s why senators Roger Wicker, R-Miss., Marco Rubio, R-Fla., and Rep. Adam Kinzinger, R-Ill., are now pushing for the establishment of a no-fly zone over Ukraine.

Kinzinger was a pilot in the Air National Guard until recently.

Lawmakers aren’t confident that the current “containment” policy is working.

This is all hypothetical. You might characterize the no-fly zone talk as “infuse to defuse.” The push reflects a slow shift on Capitol Hill among lawmakers as they try to push their way into the conflict without getting the West bogged down in battle. It’s nibbling around the edges in order to keep a broader war from spreading.

NATO would undoubtedly administer any “no-fly zone.” The United States would inevitably be a part of such an operation. Colleague Rich Edson notes that NATO just discussed the issue at a meeting in Brussels.

The Pentagon stressed that a no-fly zone would invite conflict between NATO and Russian aircraft. NATO leaders, including Secretary of State Antony Blinken, have stressed the importance of defending NATO territory, which does not include Ukraine.

“We are not going to move into Ukraine. Neither on the ground or in the Ukrainian airspace,” NATO Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg said. “The only way to implement a no-fly zone is to send fighter planes into Ukraine and the airspace and then impose that no-fly zone by shooting down Russian planes.”

Still, American lawmakers are trying to manage this fight from afar, floating ideas and suggestions. Even if they are rejected in Brussels.

Sunlight shines on the U.S. Capitol building on Capitol Hill in Washington.

(AP Photo/Patrick Semansky, File)

Here’s the problem for the U.S. if it is involved in a hypothetical no-fly zone:

The declaration of a no-fly zone isn’t self-executing. It entails enforcement. A no-fly zone is only successful when one side can maintain clear superiority in the air. That is not the case if NATO and the U.S. were to be involved with enforcing a no-fly zone over Ukraine and are up against the Russians. Enforcing a no-fly zone is an offensive action. Not a defensive one.

To enforce a no-fly zone, one side must first bomb its adversary’s air defense systems, radar, planes on the ground, radio communications technology, et al. The side enforcing the no-fly zone must be ready to engage in air combat and face enemy fire.

This crystallizes a key point in this conflict. The U.S. and NATO want to stay out of harm’s way. They don’t want to face war against Russia, a sophisticated military power.

But, a no-fly zone essentially shifts America onto a war footing.

It is impossible to be a little bit pregnant, as they say. But you can be a little bit at war.

Any involvement by the U.S. in a no-fly zone proposed by lawmakers is problematic constitutionally. A coalition of lawmakers on the left and the right would howl. They would argue that Congress must have a say in such a military commitment overseas. Article I, Section 8 of the Constitution gives Congress the right to determine the use of U.S. forces overseas if they encounter hostilities.

In other words, is bombing targets or engaging in hostilities overseas “war?” Or something else?

This is the slippery slope.

The U.S. and an international coalition enforced a no-fly zone for years in northern and southern Iraq between the 1991 Gulf War and the 2003 war in Iraq. Congress approved a resolution for the Iraq war in the fall of 1990. But the congressional authorization for military operations in Iraq after liberating Kuwait between 1991 and 2003 were murky at best.

NATO began patrolling a no-fly zone over Bosnia in the early 1990s during the civil war that broke out in the former Yugoslavia. NATO got involved due to crimes against civilians. NATO initiated Operation Deny Flight to prevent Bosnian Serbs from attacking Bosnian Muslims and Croats.

NATO saw combat for the first time in its history when it shot down Serb aircraft over Banja Luka in 1994.

The Serbs infamously fired a shoulder-mounted missile that hit the F-16 piloted by U.S. Air Force Captain Scott O’Grady June 2, 1995. O’Grady was flying a sortie enforcing the no-fly zone from Aviano Air Base in Italy. O’Grady successfully ejected and hid in the dirt for days from Bosnian-Serb forces. He sent intermittent radio transmissions. A Marine mission then crossed into Bosnian Serb territory six days later, tracing O’Grady’s signal beacon.

After picking up O’Grady, the U.S. military helicopter lifted off but encountered fire from Serb forces, narrowly sidestepping catastrophe and triggering deeper U.S. involvement.

NATO eventually unleashed a series of airstrikes against the Serbs in the summer of 1995. That ended the war in Bosnia.

That is why Stoltenberg and others oppose a no-fly zone. Such a scenario could quickly devolve into Russians taking on Americans.

So, lawmakers are pushing other approaches. A bipartisan coalition of lawmakers now wants the U.S. to bar the importation of Russian oil. House Speaker Nancy Pelosi, D-Calif., is on board.

“I think there’s a moral obligation here,” said Sen. Lisa Murkowski, R-Alaska. “I don’t want U.S. dollars to be funding this carnage in Ukraine led by Putin.”

Sen. Joe Manchin, D-W.Va., leaves a Democratic luncheon at the U.S. Capitol.

(Win McNamee/Getty Images)

Of course, there’s concern that Russia will just find another customer for its oil. Perhaps China. And even though Sen. Joe Manchin, D-W.V., is confident the U.S. can “backfill” the oil with domestic production, gas prices here could still climb.

Manchin has long fretted the impact of inflation. It’s one of the reasons Manchin killed the Democrats’ Build Back Better measure. But Manchin wasn’t worried about gas prices skyrocketing if the U.S. cut off Russian petrol.

“Inflation is a tax. This is war,” said Manchin.

Granted, this isn’t a war in which the U.S. is involved – yet. Still, Manchin believes Americans would be willing to pay more at the pump.

“I would gladly pay ten cents a gallon (more),” said Manchin.

So, lawmakers are searching for alternatives.

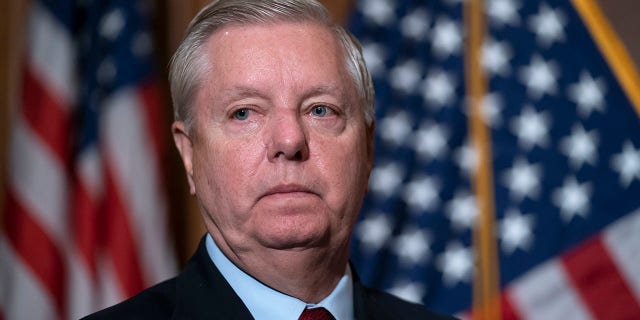

Sen. Lindsey Graham, R-S.C., waits to speak to reporters at the Capitol in Washington.

(AP Photo/J. Scott Applewhite, File)

Sen. Sen. Lindsey Graham, R-S.C., offered one option.

“Is there a Brutus in Russia?” Graham tweeted.

He followed up on Fox.

“If (Russian President Vladimir Putin) attacks a NATO nation, we’ll have World War III,” said Graham. “I’m hoping somebody will understand that he’s destroying Russia, and you need to take this guy out by any means possible.

William Shakespeare wrote about Brutus killing Julius Caesar. And, Caesar is warned by a clairvoyant that he should “Beware the Ides of March.” The “Ides” refer to March 15.

Bipartisan lawmakers went on the attack against Graham, arguing the U.S. shouldn’t advocate assassinating heads of state.

This reveals the desperation in Congress when it comes to Ukraine. Lawmakers are hamstrung. They can’t change much.

But they can do a lot of wishful thinking.

Source: Read Full Article