Focus on dangers of campus sexual violence in Biden review of Trump-era Title IX changes

As the primary author of the Violence Against Women Act, President Joe Biden has arguably achieved more progress than any other single American on the issues of domestic violence and sexual assault. Now his administration, led by Education Secretary Miguel Cardona, plans to review the Trump-era regulations governing higher education’s response to gender-based violence.

Most of the reforms made under Education Secretary Betsy DeVos have been decried by advocates and by the higher education community itself, and deserve close examination by the Biden administration. On the one hand, the department made some regulatory changes to Title IX that are hailed as progress — for example, clarifying that domestic violence and stalking constitute gender discrimination under the law.

But the new regulations also created unprecedented protections for those accused of sexual or domestic violence, far beyond a normal university disciplinary process. The regulations required higher education to morph our student conduct process into something closer to a criminal justice system, requiring mini criminal trials with live hearings and cross-examinations.

We regulate character, not criminality

The Trump reforms to Title IX claimed to correct the alleged overreach of the Obama era — that those reforms pushed higher education to take on issues better left to the criminal justice system, that the accused didn’t get their due, that increased enforcement exaggerated the specter of sexual violence on campus.

But this critique of the Obama regulations misses a couple of more fundamental points. First, universities have always — for centuries — regulated the character of our students in order to protect the quality of our educational communities. From academic cheating to fighting, from drugs to underage drinking, universities have no choice but to govern the conduct of our students. As we teach, we also work to define character and establish community norms that will forever shape students’ lives. More urgently still, we have the responsibility to make hurting other members of our community unacceptable.

Character is not a peripheral issue we can delegate to the local criminal justice system, any more than a company can delegate its human resources policies to the criminal justice system. Imagine if the only way you could fire employees accused of stealing from you, or of violently attacking other employees, was if they were first criminally convicted of the crime?

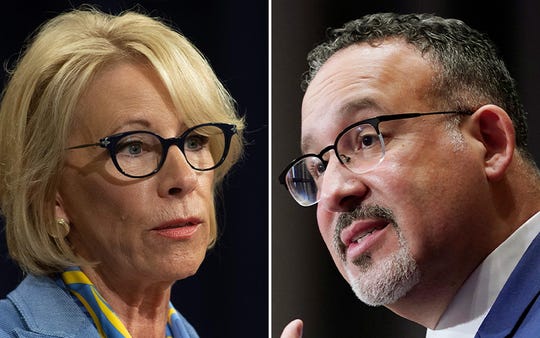

Former Education Secretary Betsy DeVos and current Education Secretary Miguel Cardona. (Photo: Getty Images, AP)

It is true that disciplining students for a serious crime like sexual assault can have a devastating impact on a student’s future and career, but that is also true when universities discipline students for cheating, drug possession or other kinds of violence. Those severe consequences are precisely why universities work hard to create a clear, predictable and fair disciplinary process. But the DeVos-era regulations make those processes unwieldy and impractical, without actually making them more fair.

Last summer, when colleges and universities had to implement the new regulations in the midst of the pandemic, I dusted off my prosecutor skills to train our Title IX staff, an unusual role for a university president. As I tried to teach them cross-examination skills, they asked me questions that had no clear answers under the new regulations. Do the rules of evidence apply? Do we make up our own? How do you define hearsay?

Stepping up: To pass a new sexual assault law, college students themselves got in the driver’s seat

These unwieldy new expectations might be worth it if they made the process appreciably more fair, but they do not. Proponents of the Title IX changes take it on faith that a formal and adversarial system is better suited to finding the truth than an investigative one, but there’s actually no evidence of that. University disciplinary processes generally focus on thorough investigations that follow the evidence. They seek truth and create rights of appeal to guard against error.

It may in fact be true that some universities, eager to avoid federal scrutiny, were sloppy in changing their own student conduct systems. The Biden administration should take a cold, hard look at the balance between fairness and justice, and make clear that while institutions must take violence on campus seriously, that does not relax the need for fairness.

We can’t let bad behavior flourish

Many of the critics’ arguments come down to this: Isn’t it more important to protect fairness rather than to punish the guilty? Shouldn’t we weigh the scales heavily in that direction? But here’s the second point I think we are missing. It matters, enormously, to get the answers right, to find the truth, to balance fairness with justice. We cannot solve process issues by throwing our hands up and allowing unacceptable behavior to flourish.

To put this in another context, universities have come to understand our obligation to protect students from violent and cruel hazing rituals. Now imagine if the federal government intervened and required us to make it as daunting as possible for potential witnesses to come forward. It would certainly provide much reassurance to students accused of hazing, but the stakes of getting the answer wrong are real, not rhetorical. Students die from hazing.

Students also die, all the time, from domestic violence. And research shows that the lifelong trauma of sexual assault — the post-traumatic stress disorder, alcoholism and suicide that result — is worse on average than even the extreme trauma resulting from combat duty.

No protection: In college I was falsely accused of sexual harassment. Men like me deserve due process.

I want to propose an alternative solution to this criminal justice system model, one that should have support from all sides and from a new president with the expertise and concern to address these issues. Let’s invest in the research to figure out how to prevent sexual assault and domestic violence, instead of trying to investigate and punish after the damage is done. Sexual violence has a massive public health impact and economic cost, yet federal research dollars devoted to prevention are remarkably limited. Much of the research money available now focuses only on the criminal justice response to rape, not to its prevention.

Universities provide important places to attempt prevention efforts, but for the most part, we are flying blind. We replicate each other’s programs often without much evidence that they work. And we do our best knowing that interventions aimed at college students probably come far too late in their psychological and moral development.

We need more serious research on how to protect our children from sexual violence before it happens — not just how to comfort them afterward. We need to know how to prevent men and women from becoming perpetrators, not just how to hold them to account after the profound harm has been done. It is time to focus on finding the answers.

Tania Tetlow, a former federal prosecutor, is the president of Loyola University New Orleans.

You can read diverse opinions from our Board of Contributors and other writers on the Opinion front page, on Twitter @usatodayopinion and in our daily Opinion newsletter. To respond to a column, submit a comment to [email protected].

Source: Read Full Article