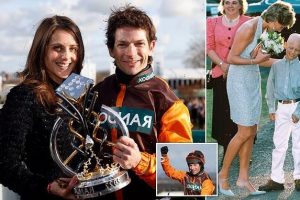

Amateur Grand National champ driven by tragedy of brother's death

How the spirit of my brave lost brother spurred me on to victory in the National: The amateur who won Britain’s most gruelling race, driven by family tragedy and cheered on by the royals, lifts the lid on a victory worthy of a movie

- Sam Waley-Cohen dreamed of winning the Grand National at Aintree as a child

- He did just that aboard Noble Yeats last week at long odds of 50-1

- Waley-Cohen has said he was driven by the memory of his brother who died of cancer aged just 20

As children, we like to indulge in crazy fantasies — that we’ll end up as film stars, astronauts, rugby professionals or maybe music moguls. For Sam Waley-Cohen, as he rode his wooden rocking horse, furiously bobbing and kicking, it was all about winning the Grand National.

‘It’s like saying I’d like to win Wimbledon or play at Twickenham,’ he says. ‘You imagine it, you dream of it. But it’s not a real thing.’

Until, 35 years later, it suddenly is.

Against all the odds, and in his final steeplechase before retiring, Sam won the 174th Grand National last Saturday on seven-year-old, 50-to-one Noble Yeats

Because against all the odds, and in his final steeplechase before retiring, Sam won the 174th Grand National last Saturday on seven-year-old, 50-to-one Noble Yeats.

It would be a career-defining moment for any jockey. But Sam is an amateur — the first to win the brutal four-mile, two-and-a-half furlong race for 32 years — who was on a horse owned by his father and only bought in February. Sam was urged on by family and friends, including the Duke and Duchess of Cambridge, but most of all, by the ghost of his late brother, Thomas, who died of cancer when he was just 20 and whose initials he has stitched into his saddle.

‘It was a fantasy, a fairy tale! The joy, the love. Even before the race, a lot of people said, “Thomas will be riding with you”. And it really did feel like he was at my back, urging me on. I feel his presence. I always have,’ he says simply.

‘The spirit of someone lives on — it’s their legacy. It helps you keep balanced when things aren’t going right and helps you use whatever talent you have, grab opportunities and make the most out of life. That’s the legacy of Thomas.’

To be fair, Sam does seem to have more opportunities (and talents) than most.

His father, Robert, the son of a baronet, founded the company Alliance Medical in 1989, which he sold for £600 million in 2007, and his mother is the daughter of Viscount Bearsted.

The family split their time between Oxfordshire and London. Growing up, he, his two brothers and sister were enviably close.

Even so, Sam couldn’t have squeezed much more out of life.

He’s been piloting helicopters since he was 21 years old, and planes since he was 18. He’s bungee-jumped out of a hot air balloon (‘I wasn’t really calculating the risks on that one’), summitted mountains all over the world, including Mont Blanc — which he climbed with skis on his back, for a rather speedier descent — and run marathons on the Great Wall of China and in London, roped to 35 others.

He has also raised vast sums for the Oxford hospital that treated his brother — including organising a roller disco attended by Kate Middleton in hot pants — and has long been credited as the person who got her and Wills to see sense during their brief separation back in 2007, though he’s characteristically modest about it today.

‘I think the right question is, does anybody put anybody back together?’ he says. ‘I think they do it themselves. It’s not like you can force it.’

On top of all that, he runs the £300 million Portman Dental Care, which has 4,000 staff in five countries, serving more than 700,000 patients — ‘it was very stressful in lockdown. Everything was shut!’ One patient he’s obliged to attend to now is his stable lad Mick Molloy — he promised to fix Mick’s gap-toothed smile with an implant if he won.

His latest victory means that Sam has become the most successful amateur jockey of his generation — adding the Grand National to his previous wins in the 2011 Cheltenham Gold Cup and King George VI Chase at Kempton and seven wins around the gruelling Aintree course.

To give an idea of the scale of this achievement, you could count on one hand the number of professional jockeys who’d expect to win all three of those landmark races in their careers. Professional jockeys, that is, who ride every day for a living, out on the gallops, training and competing in endless races each week.

Sam does it rather differently.

He’s invariably woken by one of his three children ramming their cold feet into his back in the early hours. Then he spends the day dashing about his ever-expanding dental empire, attending Zoom meetings in his car before and after races (often with a smart shirt over his father’s distinctive chocolate and orange silks).

He keeps fit (and down to just ten stone five) by running, playing tennis, skiing, boxing and working out a couple of times a week on his ‘equicizer’, a robotic training horse, ‘just to keep the legs strong’ — all rammed around the day job. ‘I try not to do anything half-cock. I’ve never wanted to play at it. I try to give it my all and my diary is always jammed,’ he says cheerily.

He’s been riding for as long as he can remember. At first it was pony club, then point-to-points, but soon he was moving his way up to racehorses, always owned by his father.

‘It’s never really been about the glory. It’s the enjoyment, the love of being on a horse, coming together with a partner, doing something you love.’

But by the time he was in his 20s, it was grief that pushed Sam onwards.

Thomas, two years younger, was diagnosed in 1995 with the rare bone cancer Ewing’s sarcoma. It was a terrible blow, but it seemed treatable, at a cost — his left leg was amputated below the knee. Not that it held him back.

After years of hard work, he has also won the acceptance of professional jockeys. It was telling that, after his victory on Saturday, fellow jockey Davy Russell came and loosened Noble Yeats’s girth and another jockey rushed over to pour water to help cool him off

Not at the Dragon School in Oxford, where he’d limp over to the cricket nets to give the sports teacher his extremely good racing tips. Or at Marlborough College, which he attended with Kate Middleton — it was through the Thomas connection that Kate (and Wills) and Sam became pals while he was at Edinburgh and they were at St Andrews. (They were among the first to congratulate him on Saturday with a message from their official Twitter account).

‘He had incredible get up and go,’ says Sam. ‘And he was extremely cheeky and lovable, and because of his illness teachers found it very hard to tell him off, so he got away with a lot.’

Including endless practical jokes using his prosthetic leg.

‘His favourite game was to leave his leg lying around on the hockey pitch or, when he was skiing, lie in the snow and pull his leg off to scare people,’ says Sam. ‘He just took the view that this was what he had in life, so he made the most of it. And he never, ever complained.’ When the cancer came back again in Thomas’s late teens, the family was under no illusion. ‘It was his third bout. We all knew he was likely to die, but it was the elephant in the room — we never talked about it,’ says Sam. ‘We knew, but we didn’t believe. You always hope that there’s something. And he kept fighting.’ Thomas died in 2004. And the family, previously so close, fell a bit adrift.

‘Initially, we all dealt with it in our own way. It was obvious when we were together that something was missing and there was an undercurrent of deep, deep sadness. It was a very dark time.’

But the following year, Sam had his first big winner, on Libertine, at the 2005 Cheltenham Festival. ‘Everything changed. It brought us all back together. There was light. Racing days are always family days now,’ he says.

Ever since, he has ridden with Thomas’ initials stitched into his saddle — to victory in the 2011 Cheltenham Gold Cup on another of his father’s horses, Long Run, beating Kauto Star and becoming the first amateur to win the race for 30 years, several more Cheltenham Festival victories and the King George VI Chase at Kempton aboard Long Run.

After years of hard work, he has also won the acceptance of professional jockeys. It was telling that, after his victory on Saturday, fellow jockey Davy Russell came and loosened Noble Yeats’s girth and another jockey rushed over to pour water to help cool him off.

All of which makes it sounds like a fairy tale. But for every victory there were endless rainy disappointments, cracked ribs, sprains and gruelling training sessions.

It was only in 2005, when he was decreed sufficiently experienced to tackle the demanding Aintree course, that a Grand National win even became a possibility.

Sam was urged on by family and friends, including the Duke and Duchess of Cambridge, but most of all, by the ghost of his late brother, Thomas, who died of cancer when he was just 20 and whose initials he has stitched into his saddle

Even then, the risks are palpable. ‘With this race, there is a big spread of outcomes. It could be the happiest day of my life, or I could end up in the local hospital,’ he says.

Right now, it’s all so overwhelming because it’s been years and years of trying, and years and years of failing,’ he says. ‘Mostly, it doesn’t go to plan. Until now.’

Goodness only knows how he juggles it all. Or how his wife, Bella, copes. Did she have any idea how relentlessly dynamic he was when they met 14 years ago?

‘We’re a great team!’ he says. ‘We met at the races and she understood about my racing commitments. But work is also a big commitment, too!’

So now he’s finally hung up his boots, on the eve of his 40th birthday, will Bella be high-fiving and heel-clicking that it’s all over, or dreading whatever mad challenge is coming up on the rails?

‘Definitely, thinking “oh-oh, what’s next!”’ he laughs. ‘I’m not sure what, but I’m sure it will find me. I’ll have to keep busy, or I’ll annoy her too much.’

And probably go a bit mad himself. Because happily, while he finds it impossible to properly give in to a holiday and flop about on a sun lounger — ‘I just can’t’ — it seems that hurling himself over enormous brushwood fences at 40mph somehow helps him relax.

‘For me, riding is freedom — you have no phone, you’re concentrating, it’s escapism,’ he says. ‘And racing is like meditation. You really have to concentrate. Your range of focus is very, very narrow. I didn’t even hear the crowd on Saturday and there were 70,000 people shouting. I didn’t hear anything.’

Even so, the race didn’t get off to the start Sam was hoping for. ‘I had a load of sand kicked in my face and the horse was going backwards. Within 50 yards of the start I was thinking: “It’s over before it’s started. What a way to finish your career”.’

But then something — or perhaps the ghost of someone — kicked in. Sam certainly thinks so.

‘The horse raised his game to the highest level, and it was one of the best races I’ve ever ridden,’ he says. ‘But there was certainly a helping hand that brought it all together.’

The Bone Cancer Research Trust, www.bcrt.org.uk

Source: Read Full Article