How foreign portfolio investors view the ‘India story’

IT, FMCG and manufacturing sectors are less attractive to foreign portfolio investors, discovers Subhomoy Bhattacharjee.

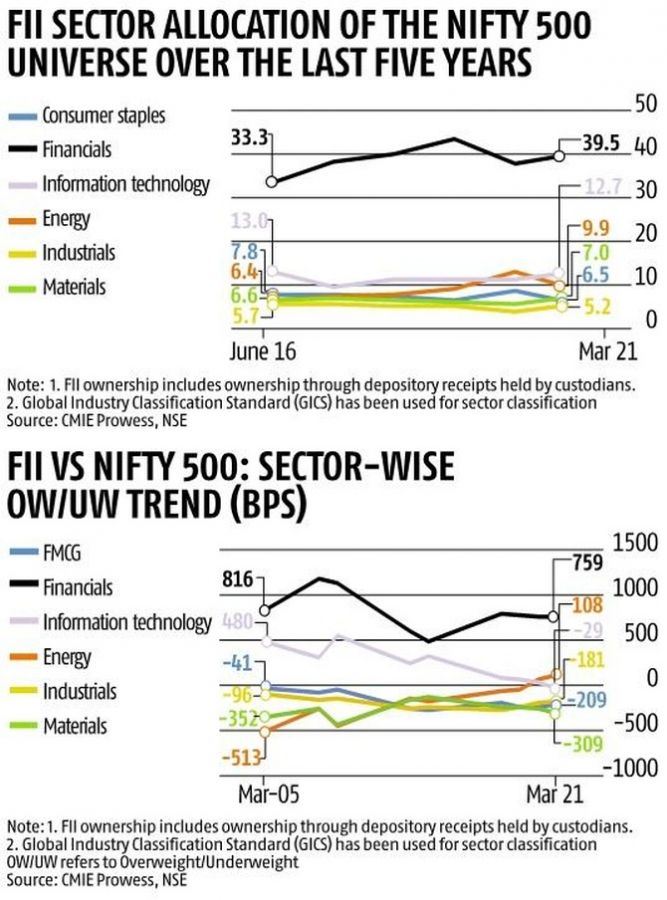

Long before the pandemic, foreign portfolio investors (FPIs earlier) regarded India as mostly ‘financials’ and ‘energy’ markets.

Not information technology, nor fast moving consumer goods (FMCG) and certainly not as an industrial powerhouse.

That impression continues. As of March 2021, in the NSE 500 universe, 50 per cent of FPI investment is in companies in the financials and energy sectors.

Given the FPIs’ combined exposure to the Nifty 500 at 40.7 per cent, this is a big deal.

If this is surprising, an NSE Market Pulse analysis out should be even more.

The analysis is like a view from 36,000 feet and evens out the quarterly fluctuations of money coming into and going out of the market.

‘FIIs have perennially remained negative on the investment theme in the economy, maintaining their underweight stance on Industrials and Materials since 2006,’ the massive study authored by NSE Chief Economist Tirthankar Patnaik notes.

Industrials means companies like those that manufacture machinery, equipment and related supplies for use in construction and manufacturing. Think L&T or BHEL.

Materials are easier to understand. These are the companies that process raw materials to produce steel, paper or fertilisers. Think Sail, think Hindalco.

Though this analysis does not explicitly say so, it is a valuable commentary on how India has pursued its economic policies over the past 15 years.

In this period, many new companies and sectors have heaved into view within India Inc.

Information technology is certainly one, but so are FMCG and automobile companies.

Riding on them, one would assume the tastes of the FPIs would have changed a lot. But except for IT, they have not on a sustained basis.

Yet if one plots how FPIs have remained overweight or underweight in their choice of investments, sector-wise since March 2006, the trend is very clear.

The NSE report shows that financials, except for a period after the global financial meltdown, has been a favourite throughout this period.

Notice that in this period, the divestment by the Indian government in the banking sector has not been strategic. No ownership transfer has taken place.

In the past few years, two insurance companies have also joined the list. The FPIs have not liked it.

As a result the combined market cap of the State-owned banks, minus SBI, just pips Axis Bank, the fourth-largest private sector bank.

It is clear where the FPI money has been going instead: It is in private sector banks and now non-banking financial companies such as Bajaj Finance. It is a thin layer of concentration.

In the energy sector, FPIs started out being underweight two decades ago.

The view changed dramatically after 2010 and has eventually superseded most others, including IT, FMCG and autos (consumer durables).

There have been periods, when IT has been preferred by them over energy but as a long-term strategy, the latter stands out.

The investments are mostly a play on the RIL scrip. The others have taken turns to be favourites — Coal India at one stage, for quite some time ONGC and now BPCL.

That both Coal India and ONGC have lost market cap despite the sustained rise in investor interest in the Indian energy play from abroad shows how badly these companies have performed.

It would seem that the waxing and waning play of the FPIs in different sectors is also a testament to the failure of the disinvestment story in India.

The concentration of risk in the financials and energy sector is mirrored in their lack of interest in both ‘materials’ and ‘industrials’ sectors.

Yet it wasn’t so at one stage. After the banks, in March 2005, both these sectors were the most sought after ones by these investors.

It has been a downhill journey in their interest, since then.

In other sectors, global investors have moved seasonally. Even in telecom stocks, there has been a recovery after the disastrous phase of 2011 to 2016.

These are the two sectors where the government at one stage had the largest play with companies such as State-owned steel maker SAIL, a clutch of fertiliser companies and a large number of processors, such as Hindustan Copper.

The on-off decisions by successive governments on the fate of these companies has caused FPIs to turn away.

Fifteen years later, the sectors have all but disappeared from their radars.

As the report notes, their turning negative is also a testament to what the global investors think about the ‘investment theme’ of the Indian economy.

This has severe implications. In FY22, the markets are fairly sure about the successful conclusion of the two divestment deals, the public issue of LIC and the strategic sale of BPCL.

But the markets do not see any company from other sectors that has the capacity to draw a similar level of investor interest in FY23.

Of the 249 operating public sector enterprises, there is precious little to offer to the markets.

They can only be offered after the government has done a massive round of investments in them to raise their value.

If that seems difficult, it is the reason the FPIs have little faith in the investment theme, refusing to build up positions in these companies.

There is another piece of corroborative data in the NSE Market Pulse report.

Since 2001, the additional capital deployed by FPIs in the Indian markets has led to a gradual rise in their ownership in a limited universe of stocks.

‘FIIs today have at least 5 per cent ownership in 71 per cent of the Nifty 500 Universe (by number of companies), even as the share has fallen slightly over the last couple of years.’

In other words, foreigners view the ‘India story’ very differently from successive Indian governments.

Feature Presentation: Rajesh Alva/Rediff.com

Source: Read Full Article