J R D Tata and the birth of Infosys

Mr Tata said a letter had arrived in his office from a young woman who had applied for the graduate engineering programme of TELCO Pune and been turned down.

‘I wouldn’t interfere with your selection process, Maira,’ he said. ‘However, I am calling you because this lady says that her rejection letter says that though she is very well qualified for the programme, TELCO Pune cannot select her because she is a woman.’

‘Why are you discriminating against women?’ he asked.

A must read excerpt from Arun Maira’s The Learning Factory: How The Leaders Of Tata Became Nation Builders.

Those who wish to build institutions should insist that the rules of the institution apply to themselves too.

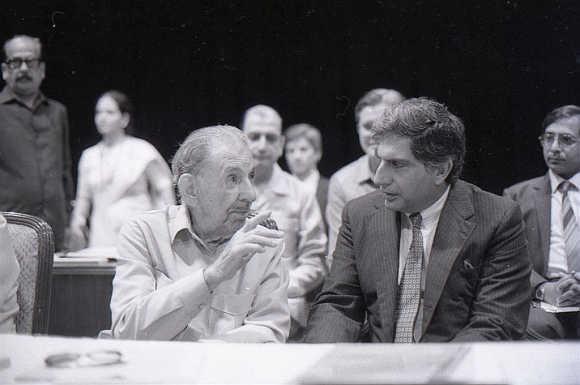

Tata Administrative Service officers attending a programme at the Tata Management Training Centre in Pune in December 1965 learned this lesson from J R D Tata himself.

It was the first programme at the centre. JRD had come to inaugurate it. He was stopped from entering the dining hall for lunch by Colonel Cama, the centre’s administrator.

JRD was dressed in a safari suit as he always was. ‘I am sorry, sir, you need to wear a tie in the dining hall — that is the rule,’ said Cama.

‘But I do not have one,’ said JRD.

‘Then I will have lunch sent to you in your room, sir,’ said Cama.

The TAS officers were aghast at the colonel’s lese-majesty. But JRD showed them what a great man he was, not by berating the colonel, but by turning around and going to his room where he had lunch.

He spoke no words. His actions spoke loud and clear. He made the point that the rules of institutions must apply equally to all if they are to be effective — and he allowed a junior officer to apply the rule even to the great JRD.

* * *

All Tata enterprises were expected to operate with ‘Tata values’.

One of the values was fairness to all stakeholders.

Another was the pursuit of excellence.

And a third, very dear to Mr Tata, was respect for the dignity of all human beings.

Mr Tata was always inquisitive about what was happening in the enterprises — not so much to instruct, which he could not because they were so diverse, but to learn.

He was particularly keen to know what they were doing on the human side of their enterprises.

He himself had written a charter for personnel management for Tata Steel, a company with which he remained closely connected throughout his 50 and more years as chairman of the group.

He would frequently query other companies about their processes for personnel management.

It was widely known that any employee of the Tata Group who felt that the Tata values of respect for human needs were not being honoured could write directly to Mr Tata in Bombay (now Mumbai).

Over 200,000 employees worked in the Tata Group all around the country. Every week some letters would arrive in Mr Tata’s office in Bombay from Tata employees around the country.

Often, they were just postcards, which were the cheapest means of communication then.

Not only was the postage for a postcard less than a letter, there was also no need to buy an envelope and a sheet of paper to write on.

An employee could write on the postcard itself and put it in the mailbox. Many postcards were addressed simply to ‘J R D Tata, Bombay’.

It was apparent that J R D Tata was well known throughout the country, because the postal system knew how to get even such postcards to him.

All mail for Mr Tata from Tata employees would be gathered by Marion Hawgood, his secretary, and given to my colleague, Ajit Gadgil, who sat beside me at the Tata Steel head office in Bombay House.

Gadgil’s job was to write to the employee, assuring him or her that the chairman was looking into the matter. And then to write a firm letter to the company concerned on behalf of the chairman, asking two questions.

One concerned the grievance itself. The other was about how the grievance had been processed by the company’s internal HR system.

Gadgil’s letters to the companies always began with the words ‘The Chairman wishes to know…’ This I know because Gadgil, sitting right beside me, insisted on dictating his letters in his booming voice to a secretary sitting across his table. In fact, the whole office would find out that ‘the Chairman wishes to know’!

One day, Gadgil got a surprise. The chairman’s peon brought a big, muscular man to Gadgil. He had arrived in the chairman’s office with his postcard.

He was taking no chances with the mail. He had brought it himself, to be hand delivered to Mr Tata.

Ms Hawgood persuaded the man that since Mr Tata was travelling abroad at the time, he might as well as meet Gadgil while he was in Bombay House.

The man was ushered to Gadgil’s table.

Gadgil looked up at the big man nervously and asked what the matter was.

The man pointed to the postcard. His complaint was that Tata Steel was not allowing him to come back to work.

Gadgil asked the man how long he had worked with the company. ‘Many years,’ the man said.

‘Why did you stop working?’ Gadgil asked. ‘Was there some problem?’

‘I don’t have any problem,’ the man said, sounding a little belligerent now, ‘but the company says I am not fit. See here how fit I am,’ he said, and pulled off his shirt in the middle of the office to reveal a large muscular chest and bulging biceps!

Gadgil thought the man was going to attack him and almost fell off his chair. He sat there open-mouthed and frozen for a few seconds until two peons rushed up and persuaded the man to put his shirt back on again.

Gadgil then asked the man to sit down and he gathered that the man was mentally disturbed. Gadgil learned from the man that the company had been taking care of his medical treatment and also that he was being paid his wages during his absence.

‘Why don’t you rest at home till you are better?’ Gadgil asked. Whereupon the man jumped up and started to pull off his shirt again to show a white-faced Gadgil how fit he was to work!

After the man had been ushered out of the office, which had been completely hushed during the drama, Gadgil wiped his forehead and grinned sheepishly at everyone. ‘For a moment I was a bit worried,’ Gadgil said, ‘He was as strong as I am!’

Some years later, in the late 1970s, when I was at TELCO in Pune, building up the human resource systems there, I was startled when my secretary said that the chairman, Mr Tata, wanted to speak to me personally.

Mr Tata said a letter had arrived in his office from a young woman who had applied for the graduate engineering programme of TELCO Pune and been turned down.

‘I wouldn’t interfere with your selection process, Maira,’ he said. ‘However, I am calling you because this lady says that her rejection letter says that though she is very well qualified for the programme, TELCO Pune cannot select her because she is a woman. Why are you discriminating against women?’ he asked.

I explained to him that graduate trainees in Pune were trained to work on the factory floor. They had to spend six months in the training division, in green uniforms like all workmen trainees, and work with their hands and on machines.

This was very hard work for women. Then the graduate trainees would have to work in shifts in the factory alongside the workers. It would not be safe for a woman.

Moreover, there were no separate toilet facilities for women in the workshops and, according to the Factories Act, we could not employ women unless we provided them separate toilets.

I thought I would strengthen my case with Mr Tata by saying we were short of money and therefore could not afford the luxury at this stage of providing separate toilets to women.

Mr Tata said, ‘Maira, Sumant (Moolgaokar) tells me that you have been to IITs and that you have done a marvellous job of attracting the best young Indians to join TELCO. I congratulate you.

‘I am wondering, though, whether you are not missing a large pool of talent by excluding women, only because you have not built toilets for them? Would you like me to speak to Sumant to consider allocating money for women’s toilets so that you can expand your pool of recruitment?’

I would not have wanted Mr Moolgaokar to have the impression that I had complained to Mr Tata. Therefore, I told Mr Tata that I would speak to Mr Moolgaokar myself.

Which I did, and we made changes in our recruitment practices, and the woman who had written to JRD was recruited.

Shortly afterwards, this woman married a man called Narayana Murthy, who founded Infosys, while she, Sudha, worked in the Tata Group.

Narayana Murthy has graciously said, very often, that Mr J R D Tata enabled him to start Infosys when he did not have any money, by giving Sudha a job.

* * *

JRD was a VVIP in India. He was the chairman of the largest and most admired industrial conglomerate in the country. He was also the chairman of Air India International.

Though he was revered by the staff at Indian airports, he did not expect special treatment when he travelled. He would always show up on time.

My colleague in the TAS told me this story. He was the executive assistant to another dynamic CEO in the Tata group.

The CEO had to send a very important letter to a secretary of a government of India ministry in Delhi, to reach him that very day.

A seat was booked for my colleague on a flight to Delhi, to carry the letter, and he got busy drafting the letter for his boss.

By the time the CEO had approved and signed the letter, my colleague realised that he may not make it in time to catch the flight.

So the CEO’s office called the airport and told them a VIP was on the way.

Time was short. The traffic, heavy. My colleague reached the airport late. However, the flight had been held up to take the VIP with the important letter to Delhi.

My colleague says he was rushed on to the tarmac in a jeep. He ran up the stairs to the aircraft door. As he was entering, he was horrified to hear Mr Tata’s irritated voice ask the stewardess: ‘Who is this VIP for whom we are all waiting?’

My embarrassed colleague says he covered his face with a folder he was carrying.

He slipped past Mr Tata, who was in the first row, to his seat at the back of the plane, past many glowering passengers who wanted to know who, indeed, was this VIP who was more important than JRD!

Excerpted from The Learning Factory: How The Leaders Of Tata Became Nation Builders by Arun Maira with the kind permission of the publishers, Penguin Random House India.

Source: Read Full Article