Thousands of Latinos were sterilized in the 20th century. Amid COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy, they remember.

Consuelo Hermosillo’s 22-year-old granddaughter didn’t want to get the COVID-19 vaccine.

The office worker at a special needs center was afraid the shot would prevent her from ever getting pregnant.

The mistrust didn’t form out of thin air.

Thirty years ago, Hermosillo, an immigrant from Mexico, worked a small catering business at home while her husband bartended and unloaded appliances at a department store. In November 1973, the 24-year-old went to the hospital for an emergency caesarian section to give birth to her third child.

The baby would be her last.

Hermosillo was sterilized without informed consent at the Los Angeles County-University of Southern California Medical Center.

“You better sign or your baby is going to die,” she said a nurse told her.

What does victory against the COVID-19 pandemic look like? USA TODAY’s vaccine panel weighs in

Her signature is scribbled on aform allowing the procedure. But she doesn’t remember signing, adding she was medicated. She didn’t know she was sterilized until a doctor’s appointment later when she asked for birth control.

A whistleblower – a residentphysician later let go by the hospital – leaked that the practice was occurring on many women. Hermosillo became one of 10 Mexican and Chicana plaintiffs in the hallmark Madrigal v. Quilligan federal class-action case, which grabbed headlines in the mid-1970s. The judge sided with Dr. Edward James Quilligan, and the women lost, but the case inspired legislation later passed in 1979 to abolish the practice in California.

The Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors in 2018 issued an apology for the coerced sterilizations. But the women did not receive reparation money as victims did in other states, such as in Virginia and North Carolina.

“As far as justice, they never received that,” said Virginia Espino, who documented the women’s stories as co-producer in a film called “No Mas Bebés,” (“No More Babies” in Spanish).

Consuelo Hermosillo. (Photo: Claudio Rocha)

Espino, a professor at the University of California, Los Angeles, and an expert in reproductive injustice, said it’s unclear how many women were sterilized at the LAC-USC medical center. The lawyer for the women who brought the lawsuit estimated “hundreds.”

Many didn’t speak fluent English and didn’t understand forms they signed, and in some cases, were coerced into signing. Many had labor complications, and were told lies that they or their babies would die if they didn’t sign.

Insidious sterilizations didn’t just occur inside that hospital. Throughout the 20th century, about 20,000 women and men were sterilized in California alone under state eugenics policies, according to researchers, including University of Michigan professor Alexandra Minna Stern. The policies targeted patients of state-run asylums or group homes. A disproportionate number were Hispanic.

As COVID-19 vaccine rollout continues, hesitancy among vulnerable communities, including Hispanic people, is piqued – and history is unearthed.

Experts and those within the communities say the skepticism partly stems from unethical medical practices that targeted people of color. Unwanted sterilizations didn’t just occur in California among Mexican women, but among Black women in the South as well as Native American women.

‘It’s not a pretty picture’: Why the lack of racial data around COVID vaccines is ‘massive barrier’ to better distribution

Between the 1930s and 1970s, for example, about a third of the female population in Puerto Rico was sterilized under population control policies that coerced women into postpartum sterilization after their second child’s birth,according to the University of Wisconsin’s Office of the Gender and Women’s Studies Librarian annotated bibliography on the topic.

The first large-scale clinical trial for contraceptives also involved Puerto Rican women: In 1956, the pills were tested on poor women in Rio Piédras, a housing project in San Juan, according to a historical review published in the Canadian Family Physician journal. The women didn’t know it was experimental.

“Women who stepped forward to describe side effects of nausea, dizziness, headaches, and blood clots were discounted as “unreliable historians,'” wrote authors, Dr. Pamela Verma Liao and Dr. Janet Dollin. The clinical trials involved pills with much higher hormone levels than today’s contraceptives.

“Despite the substantial positive effect of the pill, its history is marked by a lack of consent, a lack of full disclosure, a lack of true informed choice, and a lack of clinically relevant research regarding risk,” they said. “These are the pill’s cautionary tales.”

Angelina Zayas, a pastor at Grace and Peace Community Church that serves Chicago’s majority-Hispanic Belmont Cragin enclave, says many Puerto Rican women in her community are afraid to take the COVID-19 vaccine, citing memories of the sterilizations and experiments.

“The biggest one is fear,” said Zayas, who is Puerto Rican herself. “That’s something that they remember, which affects their judgment in getting the vaccination. They’re like, ‘Well, how can I trust?’ “

Consuelo Hermosillo listens to a recording of her voice from the trial three decades ago. (Photo: Claudio Rocha)

Who is ‘worthy’ of having children?

But history’s cautionary tales didn’t stop the injustices from happening again.

Allegations of unwanted hysterectomies performed on mostly Hispanic women at Georgia’s Irwin Detention Center surfaced last year. And between 2006 and 2010, more than 100 incarcerated women in California prisons, mostly Black and Latina, also underwent hysterectomies without their consent. The Center for Investigative Reporting broke the news in 2013.

Researchers weren’t surprised.

“If certain conditions are in place, and these are conditions that often include marginalized populations in carceral spaces, with little oversight of the authorities, those types of conditions can be right for sterilization abuse,” said Stern, author of the book “Eugenic Nation: Faults and Frontiers of Better Breeding in Modern America.”

Essential health care: For the most vulnerable Americans, these clinics are trusted, accessible and vital to vaccine rollout

“We are still very much living with … eugenic ideas of worth,” she said. “‘Who is worthy of having children, and who is worthy of raising children?’ Those are very much eugenic ideas that are alive and well and they affect policy and harm certain people.”

Under these policies, between 1907 through the 1970s about 60,000 people underwent compulsory sterilizations nationwide.

Stern is studying a dataset of 30,000 sterilization records. She has found that Latina patients in California were 59% more likely to be sterilized than non-Latinas. Hispanic men were 20% more likely to be sterilized than non-Hispanic men.

The disproportionate operations,Stern said, were rooted in a racist ideology that certain attributes – criminal behavior, homosexuality, poor health, welfare usage or education levels – were hereditary and could be minimized through preventing procreation.

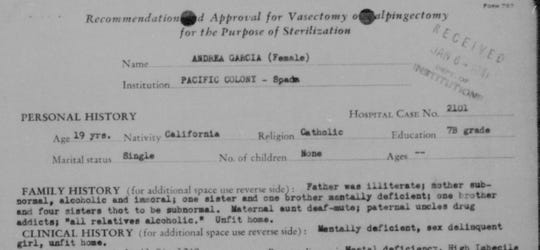

Andrea Garcia's evaluation for "recommended" sterilization, circa 1940. (Photo: BACKSTAGE LIBRARY WORKS/California state archives)

Andrea Garcia, a 19-year-old from a Mexican family, was sterilized after being admitted into Pacific Colony, a psychiatric institution, for what evaluators at the time called “truancy” and a low IQ test score.

“Mentally deficient. Sex delinquent girl. Unfit home,” reads her evaluation, an archival copy of which is included in Stern’s analyses. “Father was illiterate; mother subnormal… one brother, four sisters thot to be subnormal.”

At Pacific Colony, sterilization was a precondition for release – another coercive factor, Stern noted. Sometimes they were released back to family members, sent to be helpers in households or perform menial labor jobs.

Garcia’s mother took legal action, but lost the case.

Often, white women at the facilitycould escape the process, Stern said.

“What you have is a system in place that is stratified in such a way that is most likely to bring in certain people. A young white girl with truancy could get away with it. Unlike Andrea Garcia. She didn’t have that luxury, a safety net, she didn’t have anything,” Stern said, calling the policies and practices “dehumanizing.”

Women of color ‘robbed’ of agency, value

Virginia Espino, the historian who co-produced the No Mas Bebés documentary, said the abuses put women in unique difficulties. Some spouses didn’t trust that their wives were unwitting and thought they wanted the operations to be promiscuous. Lead plaintiff, factory worker Dolores Madrigal, said her husband took his anger out on her.

The sterilizations also sent negative messages to women of color “that their mothering is not valued in the same way,” Espino said.

“That they’re really only valued when they’re in the service of others: taking care of other people’s children, or cooking for their masters … Women of color’s bodies typically are valued when they’re used in the service of making other people wealthy.”

The women, Espino added, were “robbed of their decision-making when it comes to the kind of family they want to have.”

This man survived COVID-19: His treatment odyssey shows how complicated that can be.

On a recent morningback in California, 71-year-old Hermosillo took a break from babysitting and running the kitchens in her son’s four restaurants. Sitting on her porch in Venice, she reflected on the treatment of her and women like her.

“I think they were doing it to lower the value of us Mexicans,” Hermosillo said. “That’s what I think.”

She is grateful for her three children, but dreamed of having more. As one of her fellow plaintiffs echoed, “Se me acabo la cancion” – “my song is finished.”

Hermosillo’s older sisters had more children. As the family grew, she’d fall quiet when relatives asked when she would have more kids. She battled feelings of shame and embarrassment.

“I hated baby showers,” she said. “Something happened to me.”

As a girl in Mexico, she lived between her grandmother’s house and foster homes. She learned to be a mom at a very young age. As a teenager, she immigrated to the U.S. with her mother, and spent her days looking after her baby brother.

She didn’t tell her sisters or friends what happened at the hospital, and shared her story for the first time during the trial. She translated her love of babies and motherhood to working at the local Women, Infants and Children (WIC) Program for seven years, teaching breastfeeding classes to new moms.

She still wears a diamond necklace around her neck that she and her husband bought from one of her clients to help her with rent money.

The struggle stayswith her.

“So many years passed,” she said, “but you don’t forget.”

Reach Nada Hassanein at [email protected] or on Twitter @nhassanein_.

Source: Read Full Article