Progressives’ tax-the-rich dreams fade as Democrats struggle for votes

Reconciliation bill must be offset by tax hike: Wells Fargo Investment president

Wells Fargo Investment Institute President Darrell Cronk discusses the $3.5 trillion budget reconciliation package and the tax hikes that come with it.

Progressive Democrats, who had hoped unified party control of the government could spur transformative tax increases on multinational companies and wealthy individuals, look like they will have to settle for a more modest outcome.

Tax-code changes moving through Congress this month would still likely raise more than $1 trillion over a decade and reverse many Trump-era changes to help fund an expanded social safety net. Key pieces remain unresolved, and progressive activists hope Democrats can be swayed by last-minute pressure campaigns and the party’s desire to unite behind President Biden.

"The labor movement does not believe that there is a Democrat in either house prepared to block the president’s investment agenda for the benefit of giant corporations and billionaires," said Damon Silvers, director of policy at the AFL-CIO. "But if it turned out that there was such a person, our members would certainly want to talk to them."

Democrats are weighing how far to go, particularly on taxing multinational corporations and capital gains. They had planned to use higher taxes, tax enforcement and other policy changes to pay for their $3.5 trillion, 10-year package. The bill is expected to create a paid-leave program, extend the expanded child tax credit, offer renewable-energy tax breaks and may create a Medicare dental benefit. Each $1 trillion in tax increases over a decade is roughly a 2% increase in federal revenue.

COMPARING REPUBLICANS' $928B INFRASTRUCTURE PLAN TO BIDEN'S: WHAT'S IN EACH PROPOSAL?

Progressives are trying to keep tougher tax proposals alive. Lawmakers including Sens. Elizabeth Warren (D., Mass.) and Sheldon Whitehouse (D., R.I.) pressed last week for strong international tax rules. Senate Finance Committee Chairman Ron Wyden (D., Ore.) floated exemptions for capital-gains changes that would spare many multimillionaires but keep billionaires within Democrats’ sights.

"Now we need Congress to finish the job, to come through for the American people," Mr. Biden said in remarks Friday touting his proposed taxes on businesses and wealthy Americans.

But it is far from certain what can pass, and lawmakers have acknowledged they may need to pare their ambitions or borrow more.

The result could be a far cry from the talk of wealth taxes and repealing the 2017 GOP tax law that dominated the 2020 presidential primary campaign and weren’t part of Mr. Biden’s plans. Democrats’ slim congressional margins mean they need almost every lawmaker on board. Centrists balk at the current price tag and the taxes proposed to help pay for it, frustrating progressives. Republicans are united against higher taxes.

"Moderates and the leadership are trying to thread a needle with what is clearly a much smaller eye than some progressives would like," said Todd Metcalf, a former Democratic congressional aide now at accounting firm PwC LLP, noting that progressives may again have to accept part of what they want. "Do they take that lesson and understand that a more moderate outcome is an acceptable one because it at least advances the ball?"

There is a strong intraparty consensus to reverse some of the 2017 cuts. The corporate tax rate is likely to jump to 25% from 21%, fitting the preferences of Sens. Joe Manchin (D., W.Va.) and Mark Warner (D., Va.). That is below the 28% Mr. Biden proposed and the 35% that existed before 2017. Democrats also plan to return to the top individual tax rate to 39.6% from 37%. The Biden plan would start that top bracket at $452,700 in taxable income for individuals and $509,300 for married couples.

The tax provision generating the most Democratic angst is capital gains. To progressives, it is their clearest chance to push back against wealth inequality they have spent years decrying.

"At this pivotal moment, Congress faces a key test: will they take on three of the worst imbalances in who the nation’s tax system serves?" said Chuck Marr, senior director of federal tax policy at the left-leaning Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, referring to decisions on capital gains, international taxes and enforcement. "Will some of the wealthiest people continue to pay little or no income tax and have their bills erased when they die?"

Under current law, people who die with unrealized gains don’t pay capital-gains taxes. Their heirs do, but only on gains after the prior owner’s death and only when they sell. Democrats have spent years building the case against these rules as an unfair benefit for the richest Americans, and there is broad consensus—but not unanimity—for change.

Mr. Biden’s plan would treat death like a sale and raise the top capital-gains rate to 43.4% from 23.8%. That change would affect billionaires and others who hold appreciated stock and can avoid income taxes by borrowing against their assets instead of selling.

Moderate Democrats are wary. Members such as Rep. Cindy Axne of Iowa focus on the effects on family farmers and business owners. The Biden proposal offers a $1 million exemption to all and would let farm and business owners defer taxes as long as those entities remain owned and operated by the family. Those assurances haven’t satisfied Democratic opponents.

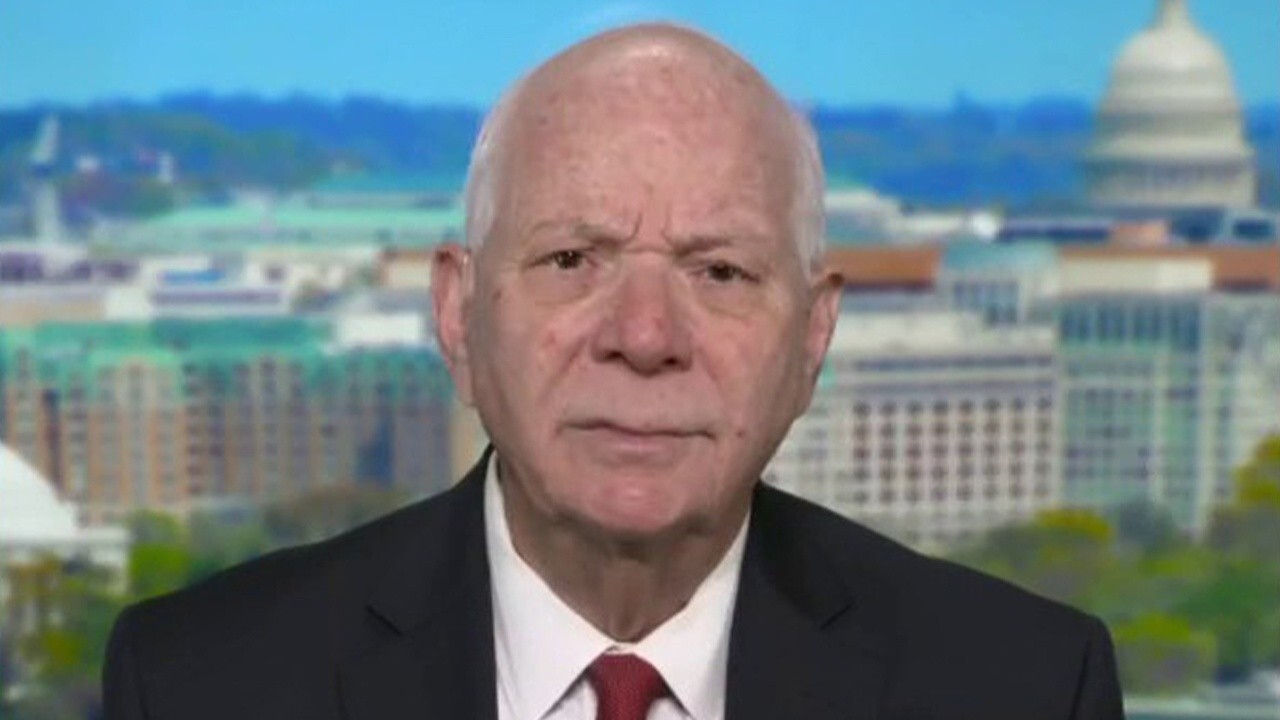

Time for Americans who’ve benefitted from past tax cuts to pay ‘their fair share’: Sen. Ben Cardin

Maryland Democrat provides insight into government spending, infrastructure and taxes.

GET FOX BUSINESS ON THE GO BY CLICKING HERE

A Senate Finance Committee options list suggests the Biden plan but with a $5 million per-person exemption instead of $1 million along with a potential $25 million exemption for family farms. One potential middle ground would impose taxes on the owner’s full gain but defer taxes until the asset is sold, rather than making death like a sale for tax purposes.

Opponents of capital-gains tax increases hide behind farms in ways that obscure that the debate is really about what happens to the very richest Americans, a senior White House official said.

Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell (R., Ky.) said on the "Guy Benson Show" last week that he prays every night for Democratic moderates and warned of the impact of tax increases.

"This absolutely undoes everything we did four years ago and that 30-year tax reform bill," he said.

On other fronts, members from New Jersey and other high-tax states are insisting on relaxing limits on the state and local tax deduction, even though the bulk of the benefit would go to high-income households.

Some lawmakers, including a group led by Rep. Brad Schneider (D., Ill.), have also questioned the need to move as far and as fast on raising international taxes as the Biden administration wants. The Biden plan would raise the minimum taxes paid by U.S. companies on their foreign profits.

"So many different industries are increasingly facing competition from around the world," Mr. Schneider said, contending that U.S. tax levels don’t have to match other countries but can’t be too far away. "We have to make sure that we are at a level that is more than worthwhile for companies to stay here."

Another piece of the administration’s international tax proposal remains unsettled. That is the so-called Shield, which denies U.S. tax deductions to companies based in low-tax countries. It is part of enforcing the broader international agreement reached by Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen, because it would eliminate potential advantages for some non-U.S. companies.

Centrist Democrats are trying to respond to business concerns about implementation, compliance costs and international pressures, said David Gamage, a former Treasury official who now teaches law at Indiana University.

"Even the moderates I talk to are…. less sensitive to the thought that we just can’t raise taxes on the wealthy," he said.

CLICK HERE TO READ MORE ON FOX BUSINESS

If Democrats can’t get the full Biden agenda through Congress, they will still have moved the terms of the debate significantly, Mr. Gamage said.

He said Democrats are no longer holding out hopes for a 1986-style bipartisan deal that closed off tax breaks but lowered rates and didn’t raise revenue. Instead, they are willing to consider revenue-raising ideas that weren’t on the table during the Obama or Clinton administrations.

"The long-term trends are much more favorable to substantial progressive tax reforms than has been the case for the past 20, 30 years," Mr. Gamage said.

To read more from The Wall Street Journal, click here.

Source: Read Full Article