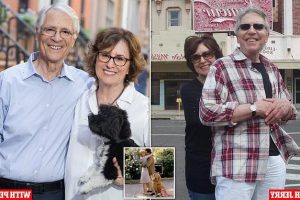

DELIA EPHRON: How my life turned into the plot of the romcom I wrote!

You’ve Got Mail – or how my own life turned into the plot of the romcom I wrote! Screenwriter DELIA EPHRON speaks about grieving for her husband when an email from an old flame pinged into her inbox

Delia Ephron is a best-selling author and screenwriter whose movies include You’ve Got Mail — an online romance starring Tom Hanks and Meg Ryan — which she co-wrote with her sister Nora. In her remarkable new memoir, she writes about the death of her husband after 33 years of marriage.

But it’s what happens next that’s astounding: at the age of 72, nearly 20 years after the release of You’ve Got Mail, Delia finds herself exchanging romantic emails with a stranger…

I knew my husband was dying in June. He’d been living with a terminal diagnosis for six years but suddenly his cancer turned aggressive.

We redid our wills. I began to rehearse being alone. I’d go to coffee with a friend or to some event and on the way home, I’d tell myself: ‘Imagine you are coming home and Jerry isn’t there. He isn’t there to share, to listen, to rant, to laugh, to comfort.’

Preparing for some unknown, for life without him, I also noticed that I needed to feel alive. I needed to walk fast on the street, get out, engage with friends. Dying was not where I wanted to be. So there was a war going on inside — the need to be with Jerry, with his dying, and the need to be separate.

I had met Jerry in my early 30s when I was finding my voice as a writer. My book came out the first year we were together. I remember hearing him in the next room laughing as he read it.

Jerry was a playwright and screenwriter. We fell for each other head-spinningly fast when a mutual friend brought him by my apartment. I felt I’d been looking for Jerry my whole life and he felt the same.

Before Jerry, I wasn’t someone who knew much about love. I was raised in Beverly Hills, the daughter of screenwriters. My parents were a team. They wrote Desk Set (Katharine Hepburn and Spencer Tracy), Daddy Long Legs (Fred Astaire and Leslie Caron), No Business Like Show Business, in which Marilyn Monroe sang ‘We’re Having A Heatwave’.

I’d been raised with expectations — all four sisters were expected to be writers — but my mother was cold to me and a drinker. She died in her 50s of cirrhosis. My dad was more loving but troubled and needy, a manic-depressive as well as a drinker.

Jerry was completely on my side. I’d never experienced that. I hadn’t believed it was possible. He truly loved me and nurtured my talent. I could never have found my way without him.

I couldn’t have children, and, after discovering that, I tried medically, but not too hard. Being a mom had never been something I dreamed about.

Now [after 33 years of marriage] Jerry wasn’t going to be here to love me or to talk to me. To have conversations with me about everything. Stuff. What was on his mind. What happened on the street. Why something made him or me happy or drove one of us crazy.

At some point in September, my husband’s prostate cancer had spread to his bones. If I wrapped him in my arms, I risked hurting him, but every night when we fell asleep, he laced his fingers through mine. He didn’t talk much about actually dying. He said the only thing he worried about was my being alone.

By Wednesday, October 21, 2015, he was completely bedridden and foggy, and I was crying. I cried in a cab on the way to get a blow-dry. Do I need to explain why I was getting a blow-dry? I can’t, except to say it’s an addiction and I did not leave Jerry alone.

At 8pm, the night nurse showed up. This was the first night I didn’t sleep with Jerry. I couldn’t sleep with the nurse staring at me.

Sometime after 3am, I woke up bone-tired, then went upstairs. Jerry gasped. And that was it. He was gone.

What I remember about the days after was how alien it was. With Jerry gone, I was dislocated, living in an unknown land. I was exhausted to the point of dizziness and at the same time charged on adrenaline. The apartment was full of friends and relatives. I remember coming downstairs from a failed nap and seeing a crowd in the living room, all of them chatting like it was a party. I felt as if I’d walked into the wrong house.

December 2015 — one and a half months after Jerry’s death. It must have radiated off me, the sense that I was fractured. That I had suffered a blow. Did I look sad? I’m sure.

In almost every conversation, I felt as if I were disregarded or not heard. At the cheese counter at the market; discussing a leak in the wall. Even waiters suggested I might order something other than I did.

There were tons of things to deal with. Jerry’s bank and credit card accounts had to be closed. Then there was the will. Death stuff.

I wanted to dream about Jerry. A dream was the only way I could spend time with him. I was thinking about that a lot, hoping that by thinking, I could make it happen. And I did. And it felt absolutely real, as some dreams can.

In the dream, Jerry said: ‘I want a divorce. I’m leaving you.’ I knew he meant it. Jerry could be tough — not often, but when he was, there was no changing his mind. I left the room and came back. I said: ‘Well, I know you want to divorce me, but we can talk, can’t we? I mean, if I want, can I just come over and talk to you?’

‘No,’ he said. He walked down a hall and disappeared. I woke up stunned. Was that Jerry? Was that an actual visitation?

I don’t think dead people talk to you in dreams. That’s always been my belief. I don’t think dead people talk to you at all. I’m not religious or spiritual.

Extremely agitated, I thought about the dream for days. I told myself: ‘This is my dream. I created it. And in it, Jerry is telling me he’s gone. He’s left me. He was clear about it. He is never going to be in my life again. Except in memories. Get used to it.’

People always asked: ‘How are you?’ Emphasis on the ‘are’ so I knew it was a serious question. But I never had a clue how to answer it.

How did I distil this sad/lonely mess of me into something simple? I couldn’t articulate my grief. And to try seemed to cheapen Jerry’s memory.

They were being kind and thoughtful, but I disliked it. I know I would have disliked it more if they hadn’t asked and if they had acted as if I were the same person I’d always been.

I avoided larger gatherings like book parties or any sort of party. I’d discovered, after trying a few, that I felt lost. More than that, I was almost panicky, looking around the room, wondering whom I should try to talk to.

Also, I felt that wherever I was, it was the wrong place. I really should be someplace else. But where? There was a continual sense of dislocation that I couldn’t correct.

Oh, I still had my apartment, but, much as I loved it, it was Jerry who made it home. I was, in a sense, homeless. Feeling like a stray.

In March, I made my first decision to move on: I decided to shut down Jerry’s landline. But when I asked for his landline to be disconnected, somehow the company also disconnected the [broadband] on the other landline. It took nearly a week to get my internet back, and it was still erratic. That summer, I wrote an op-ed for the New York Times about why I absolutely hate my phone and internet provider.

I got hundreds of comments as well as emails sent to me through my website. One man asked me to have drinks with him at the Carlyle.

Drinks at the Carlyle? I discussed this development with my girlfriends. It was agitating to think of meeting a new man. I was pretty sure from his email that this man wasn’t my type.

I emailed the man back and told him that I wasn’t sure I was ready to see someone new. I wanted to think about it. In spite of this, he emailed (I began to think of it as bombarded) me almost daily, suggesting other places to meet, all fancy, people whom I could talk to who knew him, like someone from Goldman Sachs. Was that supposed to charm me?

I went so fast from feeling flattered to feeling bullied.

My mother had given me heaps of ambition — something I am immensely grateful for — but no guidance on men. It took some therapy, and many unloving boyfriends, for me to find my confidence.

Somewhere buried in me was still that vulnerable single girl. That feeling of wanting to be wanted, that girl I was before I became the woman I am. My sensibilities had been so rattled by Jerry’s death, I could feel that young girl banging around inside me, waiting to take me down.

I thought — I remember this clearly — that there were only two kinds of men I could ever be interested in, writers and shrinks. Because they both have emotional curiosity.

This is ridiculous, of course. Lots of other men have emotional curiosity, and probably many writers and shrinks don’t. Nevertheless, that childish, immature, but hopeful thought passed through my brain.

October 22, 2016 — the one-year anniversary of Jerry’s death. I have been able to write. I’m able to sleep. I love my friends. Our dog Honey gives me a dose of magic daily.

I still get lost when the sun goes down. The silence in the apartment is loud. But I guess I’m okay.

Three days later, I received this email through my website: ‘Dear Delia — Peter Rutter here. We know (knew) each other. Your big sister fixed us up when you were at CT College, I at Columbia…

‘I am now a Psychiatrist/Jungian Psychoanalyst in the [San Francisco] Bay area, and writing you because of several confluences: [your latest novel] Siracusa, and your Times piece about disconnecting your late husband’s phone, which closely matched my attempts to do so with my late wife’s phone… She died in March of lung cancer (not a smoker).

‘I’m trying to heal up by hiking in and out of the Grand Canyon — done it twice in the past few months. I’m still working. We had two kids, now in their 30s, and a blessed granddaughter came along in September. If you have any interest in further conversation (clearly I do) email me or phone. Be well, Peter.’

It was a nice note. Relaxed. Easy. Friendly. The amount of confluence was eerie. He came blessed by my sister Nora. His last trip with his late wife had been to Siracusa, where my novel was set. It’s a falling-down place in Sicily. How likely would that be?

I had no memory of having a date with him. I Googled. There was his practice, in Marin County [California] and San Francisco. But I could not find a photo of him. But then I found books he’d written. Good grief. How amazing. He was an expert in sexual harassment.

I waited a couple of days, God knows why.

Delia to Peter, October 29: ‘Hi Peter, Good to hear from you… I’m embarrassed to say, I mean truly, that I have absolutely no memory of our date and I hope you don’t either. Although being an analyst, you probably have better recall. Nora fixed us up? How did you know Nora?’

From Peter the next day: ‘Hi Delia, What a delight to wake up to your message, this dreary, rainy, darkening, always beautiful Northern California day… Nora: I had a summer job at Newsweek in 1962 as a nascent sportswriter… From that arose my meeting you, and I actually do remember much of it. We had several dates, including the evening your parents took us to see Take Her, She’s Mine on Broadway…’

There were two attachments. His book and a photo. He was in a canoe. Some red-rock canyons behind. He looked just great.

How could I not remember him? We’d had several dates? He’d met my parents. He went to Take Her, She’s Mine with them and me. My parents wrote that play. It was on Broadway my first year in college.

I have a friend, Alice, who is a practising psychologist living in the Bay area. We went to high school together. She is my oldest friend. I called her.

‘Oh my God, is he interested in you?’ she said.

She’d met Peter, she knew his wife had died. She didn’t really know him, but she did know a bit of his story — that he and his wife had been divorced for years before they got back together and married again.

I liked that. It made him more interesting. Wondering later why it made him more interesting, I guess I thought he wasn’t conventional. And maybe he had more room for me in his heart. Two days later, we exchanged five emails.

From Delia to Peter: ‘Good grief. You went with me and my parents to Take Her, She’s Mine. I don’t even know where to begin with that. Several dates? The obvious question: Did you kiss me? A yes or no answer will be fine…’

Peter to Delia: ‘I felt the tremor of your email in the middle of the night… A yes or no answer on the kiss back then? No. [ ]

‘These are the easier answers; there is so much more to say about everything else in your/my messages.

‘Do you feel up to having a phone conversation? I’d like to whenever it might suit you. You have my number or send me your number and a good time to call.

‘Goodbye for now, Peter.’

Delia to Peter: ‘…Okay, seriously, I don’t understand this connection, which clearly exists, I mean, I’m a little gobsmacked and I am scared, actually plain scared, and scared of missing Jerry more by talking to you. I don’t mean it the way it sounds. I’m sure you know exactly what I mean and will miss your wife more by talking to me…

‘And yet there is something about death that makes me more interested in life than ever. Paradox is everything, but truly I can’t believe I am emailing a stranger something this personal. So I am confused by all this. Let me think about it overnight.’

From Peter to Delia: ‘Of course: that is, to your thinking about it overnight… I think you got the meaning of my thus far unsaid, therefore empty-bracketed thoughts/feelings: [ ] They are plentiful.

‘Yet there are a very few things for now that I do want to say: there is no one else, nor has there been since Virginia died, nor did I expect such.

‘And yes, I have already consulted Virginia, not that I really know how to do such a thing, but cried when I did it, knowing that she would wish me to go ahead and find out what this is. I believe our hearts will tell us how to do this.’

I would have been out of my mind not to talk to a man who wrote a note like that.

We set a date for a call. I wrote him that I was going to buy boots. Peter sent me a song, Come In Stranger, by Ian and Sylvia.

He wrote: ‘In addition to your boots, two minutes to help prep you for an upcoming conversation with your new stranger.’

Come In Stranger is a wonderful folk song that dates us both: ‘Stay long enough so the one I love won’t be a stranger to me.’ Then he sent me another: You Were On My Mind. And then another as we heated up: This Wheel’s On Fire. He was courting me.

Our first phone call was on Tuesday, November 1. I called Peter from my landline, sitting on a couch in Jerry’s office. Why did I put myself there? I guess to make it as difficult as it could be for me.

I was so anxious. I would hear his voice. Would he have a nice voice? He would be real now, not just an email personality.

All I remember was wanting to get off the phone. His voice was just fine, not smooth like Jerry’s, deeper, with a roughness to it.

I said I had to get off 15 minutes after we started talking. He was a bit surprised and asked if he could call me later, after his next patient.

I said okay. I talked to him an hour later in my office. Not for long. I am someone who needs to adjust to everything. A few steps forward, a few back — that’s me. That has always been me.

And one single thing about all this: We were both 72 and age meant nothing. We were getting as loopy, as obsessed with each other as anyone falling under the spell of romance.

Short emails were now flying back and forth, and when Peter had to drive to Nevada, we talked the four hours there and the four hours back.

We talked about everything, God knows. We were simply voices connecting, spilling our thoughts. Getting to know each other. It was a fantastic adventure.

Very late at night, Delia to Peter, nine days after receiving his first email, only a subject line: ‘I MISS YOU.’

Later than that, Peter to Delia: ‘Likewise, sweet D.’

We hadn’t yet met. We had a plan, though. Peter would fly to New York to see me the following weekend. In the meantime, my days were occupied with trading emails, my nights with long phone calls.

It was as if the universe had given us a gift — to experience all the madness and thrill of falling in love at a time in our lives when that was supposed to be over.

It was happening at the speed of light. Which is the way it had happened only one other time in my life, when I met Jerry.

The night before we met, Peter to Delia: ‘Precious one. Hope you are sleeping peacefully and let this touch you deeply when you awake. Delia, je t’adore.’

Adapted from Left on Tenth: A Second Chance At Life by Delia Ephron, published by Transworld at £16.99. © Delia Ephron 2022.

To order a copy for £15.29 (offer valid until April 10; UK P&P free on orders over £20), visit mailshop.co.uk/books or call 020 3176 2937.

Source: Read Full Article