John Clunies-Ross, who died at 93, ruled Cocos Islands for 30 years

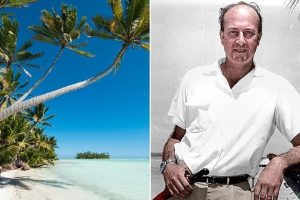

Was the British king of paradise really a parasite? Descended from the Scottish seafarer who discovered them, John Clunies-Ross, who has died at age 93, ruled over the Cocos Islands as his private fiefdom for 30 years – until storm clouds gathered

- John Clunies-Ross ruled over the Cocos Islands for more than three decades

- Barefoot king of the Cocos strode about his domain with a ceremonial dagger

- But he was also their sole employer, landlord, school teacher and law enforcer

- He lived with his wife and five children in style in the mansion Oceania House

For more than three decades he ruled over shimmering coral cays scattered across a remote corner of the Indian Ocean with all the authority of a benign but absolute monarch.

To his few hundred subjects he was more than the barefoot king of the Cocos Islands who strode about his domain, with a ceremonial dagger strapped to his waist the only symbol of his power.

John Clunies-Ross was also their sole employer, landlord, school teacher and law enforcer, and he lived with his wife and five children in some style in the ancestral mansion, Oceania House, built with bricks from Scotland, and which boasted eight bedrooms, a ballroom, spiral staircase, teak panelling, and 12 acres of walled gardens.

As magistrate he had abolished corporal punishment on the island, but a cat o’nine tails hanging prominently in the court room was an uncomfortable reminder it could be brought back.

Not that there was much to punish as crime was virtually non-existent.

The most common offence was marriage before the age of 16 for which both bride and groom were liable to a flogging that, by custom, the husband-to-be would gallantly take in a double measure — at the conclusion of which the union would be recognised.

But when, in the 1970s, the modern world poked its nose into the running of this private fiefdom, 1,700 miles northwest of Perth, Australia, Clunies-Ross, who has died aged 93, found himself a king without a kingdom.

For more than three decades John Clunies-Ross (pictured in September 1972) ruled over the Cocos Islands in the Indian Ocean with all the authority of a benign but absolute monarch

An Australian government report likened the workers on the coconut plantations to ‘slaves on the estate of a benevolent slave-owner’ in pre-Civil War America.

The UN sent a committee to examine conditions for the locals, and Australia — to whom Britain ceded sovereignty in the 1950s — wanted to end what for 150 years had been an outpost of Scottish feudalism.

As a result, Clunies-Ross, descendant of the Scots-born maritime adventurer who in 1825 had chanced upon the atoll, run up the Union Jack and claimed the territory for Britain in the name of King George IV, was forced into a life in exile.

Announcing his father’s death last month, his son and heir — also called John — said the claims his father was akin to a slaver were absurd, and that he had never got over being obliged to leave the Cocos.

‘It broke him, he never really came home. It was the power of the government against a single person. There was a rush to change things but no plan.

‘Cocos is still dealing with the results of that — including massive unemployment.’

Clunies-Ross senior, who had spent much of his childhood in Britain and studied sociology at the University of London and colonial administration at Oxford, assumed control of the Cocos Islands — the fiefdom had the look and feel of a Scottish country estate but the women wore headscarves and street names were in Malay — after World War II.

His father had died of a heart attack brought on by the shock of a Japanese air raid on the islands in 1944.

Known in local patois as Tuan (Sir) John or ‘King Ross V’, Clunies-Ross was the great-great-grandson of the founder and little had changed in the administration of the islands in the years since.

Generations of Cocos residents were born, lived and died on this horseshoe-shaped group of 27 islands many miles from civilisation. Those who left were not permitted to return, even if they could afford to, which most couldn’t.

But this far-flung location did have some benefits: islanders were free of most infectious diseases, even the common cold.

The islands’ economy depended on harvesting copra, the kernel from which coconut oil is extracted. As plantation owner, Clunies-Ross issued his own currency to pay his employees’ wages, first in paper and then plastic, redeemable only at the company store.

But he was more than the king of the Cocos Islands (pictured) who strode about his domain, John Clunies-Ross was also their sole employer, landlord, school teacher and law enforcer

Workers later complained this was a form of servitude because the Cocos rupees were worthless outside the islands, making them totally dependent on their ruler.

One of his first acts was to end the practice of adolescent girls being kept under lock and key to await their master’s pleasure, and to abolish the tradition of house guests being presented with a nubile girl as an act of hospitality.

At the same time other practices remained unchanged.

‘The key to the whole bloody business is free or cheap labour,’ a family member once inadvertently disclosed to a journalist, letting slip the reality of their so-called benevolent autocracy.

Two generations of Clunies-Ross men had married Malay girls but despite such integration, the community operated like a medieval estate. Clunies-Ross had married a fellow Oxford student, Daphne Parkinson, from Lancashire in 1951.

She later recalled her arrival in the islands. ‘We went down on a boat and I remember John saying, ‘I can see the islands’, but I couldn’t see anything, just a grey smudge on the horizon, and I wondered what I had come to.’

Clunies-Ross said he thought of the islanders as ‘my people’ but reports emerged that the supposedly paternalistic ruler’s wishes were actually carried out by a loud, swaggering drunkard known as the ‘estate manager’.

As school master, Clunies-Ross barely troubled to offer any education in geography, leaving the population in a state of ignorance of the world beyond their shores.

Not that the outside world knew much about the Cocos Islands — though it did feature in a World War I naval battle between a German cruiser and an Australian battleship.

But Clunies-Ross came to appreciate the island’s strategic importance, and in 1951 signed an agreement with the Australian government to build an air base, which opened an air route between South Africa and Australia.

It was the arrival of the Queen and Prince Philip after a royal tour Down Under in 1954 during which a white-suited Clunies-Ross — unusually wearing shoes for the occasion — was their host, that put the islands firmly on the map.

The islands had enjoyed a chequered history to that point.

First discovered in 1609 by British Captain William Keeling of the East India Company, they were not charted for another 196 years.

Then in 1825, Scottish trader Captain John Clunies-Ross, originally from the Shetlands, chanced upon them and planted fruit trees. By the time he returned with his family two years later there was a rival claim.

Alexander Hare, a wealthy English merchant with a taste for polygamy, had dropped anchor with 40 Malay women intent on establishing a harem far from prying eyes.

The libertine and the Scot were uneasy neighbours. Eventually Hare retreated to a small rock known as Prison Island, where his wives were locked up, until he’d had enough of island life and fled — leaving the women behind.

In the 1970s, the world looked into the fiefdom and 1,700 miles northwest of Perth, Clunies-Ross, who has died aged 93, found himself without a kingdom. Pictured: Cocos Islands

Meanwhile Clunies-Ross planted coconut palms, imported labourers from what is modern-day Indonesia and began trading with Britain and the East Indies.

Charles Darwin visited in 1836 on his ship HMS Beagle and found the population ‘nominally in a state of freedom as regards their personal treatment, but in most points they are considered slaves’.

Queen Victoria had granted the family the islands in perpetuity in 1886 and the status quo remained largely unchanged through succeeding generations of the British-educated Clunies-Ross family. It may have remained that way until an Australian official arrived in 1972.

‘Up to that time I had had a good press,’ Clunies-Ross later recalled, ‘rather romantic but general a favourable one. Then it changed completely.

‘The man came up here on a visit and wrote a wretched report when he got back in which he compared me to a southern American slave owner. He leaked it to the Press and it took off.’

In 1978, Australia demanded Clunies-Ross sell the islands, and under threat of compulsory purchase he was paid £2.5 million.

Although he, his wife and five children were allowed to retain their home and 12 acres of land, the days of the King of the Cocos and control of its people was over.

Bitter at the turn of events, the family moved to Perth and invested the money from the sale in a shipping line, which collapsed in 1986.

Clunies-Ross retired to suburban obscurity but the family links with the Cocos (population under 600) continue.

His son John, known as Johnny, lives there, breeding giant clams he sells to the aquarium industry in Europe and the U.S.

‘We looked after the community, generation after generation, pretty well,’ he has said.

‘We had 100 per cent employment, 100 per cent healthcare, pensions, paid holidays — all the things people aspire to as the touchstone of social democracy. Now they have social democracy, but everything else has gone.’

Source: Read Full Article